Around the time that I was dreaming of seeing my first novel appear in print, I studied a good many books which my contemporaries had managed to get published. Examples included Ann Cleeves and Peter Robinson, whose careers I followed right from the start, and Lesley Grant-Adamson. I also bought a novel by Minette Marrin called The Eye of the Beholder; like Lesley, she was published by Faber, which seemed a good recommendation.

However, for reasons I can't now recall, I put Marrin's book (first published in 1988 and paperbacked a year later) aside - and, alas, never got back to it. Until now, that is. I was curious to catch up with it at long last for a number of reasons, not least because Marrin has never returned to the genre. Her name was, however, familiar for many years as a Sunday Times columnist; no doubt she decided she preferred to concentrate on journalism.

The protagonist is a television producer, and while working in France she stumbles across a slightly mysterious death; later, another death occurs, which seems to her to be linked. The story begins pretty well, but suspense falters in the middle, a sign perhaps of Marrin's inexperience as a writer. There's some stuff about art history which I found less than gripping. But then the book picks up pace and interest, and the later scenes are genuinely gripping. The date that the book first appeared is relevant, because of the Cold War aspect of some parts of the plot. And there's a low-key feeling about the way the story unfolds that reminded me a bit of a book I read long ago, Roy Fuller's The Second Curtain.

Marrin is a capable writer, and there are some witty and thought-provoking lines which make me regret that she didn't continue as a novelist. Her heroine reads mysteries, so Marrin must like the genre, but perhaps she found it insufficiently rewarding financially. The Eye of the Beholder is, I think it's fair to say, a book of promise rather than major achievement, but the promise is so considerable that one wishes it had marked the start of a crime writing career.

Friday, 31 August 2018

Wednesday, 29 August 2018

The Publishing Revolution

Technology drives me to distraction when it doesn't work, but in calmer moments, I often reflect on the benefits it has brought, not least to readers and writers. I don't think it's an exaggeration to say that publishing has been revolutionised in recent years by technological advance. Now that it is possible to publish books cheaply, either in print form, or as ebooks, many titles are available that would have been impossible to find in the past.

I'm not just talking about reprints of classic crime novels. Authors of non-fiction are benefiting hugely. Of course, technology has (in a sense) impacted harshly on non-fiction books. So much information is available online at the click of a mouse that traditional publishers may well be wary about taking on new titles unless it's very clear that there's an eager readership for them. But two books landed on my doorstep yesterday that reminded me of those benefits I've mentioned.

The first is a book I've mentioned here previously, the updated version of the late Bob Adey's Locked Room Murders. John Pugmire and Brian Skupin have rendered crime fans a great service by revising this splendid book, which in its original editions is almost impossible to find at a reasonable price. The book appears under John's Locked Room International imprint, and LRI is one of those small presses which have made admirable use of technology to make available books which are fascinating yet which might have a relatively limited readership. Strongly recommended - and I can't wait for the promised further update of Bob's splendid work...

The second is John Goddard's Agatha Christie's Golden Age, a chunky and in-depth study of the Poirot stories, with an intro by John Curran. This book is published by Stylish Eye Press, an imprint set up by John Goddard himself. Again, this is a volume which might not sell in the tens of thousands yet which seems to be a very worthwhile venture. I'm looking forward to reading it, but without that technological progress I've mentioned, I'd never have had the chance. Something to remind myself of the next time my PC breaks down!

I'm not just talking about reprints of classic crime novels. Authors of non-fiction are benefiting hugely. Of course, technology has (in a sense) impacted harshly on non-fiction books. So much information is available online at the click of a mouse that traditional publishers may well be wary about taking on new titles unless it's very clear that there's an eager readership for them. But two books landed on my doorstep yesterday that reminded me of those benefits I've mentioned.

The first is a book I've mentioned here previously, the updated version of the late Bob Adey's Locked Room Murders. John Pugmire and Brian Skupin have rendered crime fans a great service by revising this splendid book, which in its original editions is almost impossible to find at a reasonable price. The book appears under John's Locked Room International imprint, and LRI is one of those small presses which have made admirable use of technology to make available books which are fascinating yet which might have a relatively limited readership. Strongly recommended - and I can't wait for the promised further update of Bob's splendid work...

The second is John Goddard's Agatha Christie's Golden Age, a chunky and in-depth study of the Poirot stories, with an intro by John Curran. This book is published by Stylish Eye Press, an imprint set up by John Goddard himself. Again, this is a volume which might not sell in the tens of thousands yet which seems to be a very worthwhile venture. I'm looking forward to reading it, but without that technological progress I've mentioned, I'd never have had the chance. Something to remind myself of the next time my PC breaks down!

Monday, 27 August 2018

Taking a fresh direction as a writer

Writing careers fascinate me, and I know from questions put at the "Life of Crime" talks I've been giving up and down the country for many years that they also fascinate a great many readers. A major part of my thinking in starting this blog more than ten years ago was to supplement those talks by giving further insight into the life of a crime writer who was far from being a household name. Since then, my career has moved in a very happy direction, but I remain fascinated by the rollercoaster nature of literary lives.

It's often said that these days, it's as hard to stay published as it is to become published in the first place, and there's at least a degree of truth in that. So what can a writer do? Regular readers of this blog will know that I am a strong believer in keeping one's writing fresh. In my case, this means varying the nature of what I write - short stories as well as novels, fact as well as fiction, writing about other people's books even more than about my own. With each Lake District Mystery, I've tried to do something a bit different from the last book - this was especially the case with The Dungeon House, the most recent entry in the series.

Gallows Court, however, is very, very different from my earlier books. It took a long time to write, and naturally I have been nervous about how it might be received. There are various stages in that process of getting reaction. First, the agent's reaction. Happily, that was very positive. Second, the reaction from publishers. Here, I was thrilled to be taken on by Head of Zeus, a really excellent publisher. Third, what would good judges say? Advance copies of the book were sent to a splendid mix of leading authors, from Lee Child, Peter James, Stephen Booth, and Peter Robinson to Ragnar Jonasson, Peter Swanson, and Shari Lapena I've been truly overjoyed by their comments.

And finally, what do readers and reviewers say? Well, I'm holding my breath, but I've been gratified by the very first review, which has just appeared on the In Search of the Classic Mystery blog. I'm so pleased that Puzzle Doctor approves the book. When you send a book out into the world, you have to accept that not everyone will love it; that's life. But it's certainly great for morale if initial reaction is largely favourable. And that is especially true when one has taken the risk of striking out in a fresh direction.

It's often said that these days, it's as hard to stay published as it is to become published in the first place, and there's at least a degree of truth in that. So what can a writer do? Regular readers of this blog will know that I am a strong believer in keeping one's writing fresh. In my case, this means varying the nature of what I write - short stories as well as novels, fact as well as fiction, writing about other people's books even more than about my own. With each Lake District Mystery, I've tried to do something a bit different from the last book - this was especially the case with The Dungeon House, the most recent entry in the series.

Gallows Court, however, is very, very different from my earlier books. It took a long time to write, and naturally I have been nervous about how it might be received. There are various stages in that process of getting reaction. First, the agent's reaction. Happily, that was very positive. Second, the reaction from publishers. Here, I was thrilled to be taken on by Head of Zeus, a really excellent publisher. Third, what would good judges say? Advance copies of the book were sent to a splendid mix of leading authors, from Lee Child, Peter James, Stephen Booth, and Peter Robinson to Ragnar Jonasson, Peter Swanson, and Shari Lapena I've been truly overjoyed by their comments.

And finally, what do readers and reviewers say? Well, I'm holding my breath, but I've been gratified by the very first review, which has just appeared on the In Search of the Classic Mystery blog. I'm so pleased that Puzzle Doctor approves the book. When you send a book out into the world, you have to accept that not everyone will love it; that's life. But it's certainly great for morale if initial reaction is largely favourable. And that is especially true when one has taken the risk of striking out in a fresh direction.

Friday, 24 August 2018

Forgotten Book - The Hanged Man of Saint-Pholien

Georges Simenon's early (1931) Maigret novel The Hanged Man of Saint-Pholien, has also had several other titles. These include The Crime of Inspector Maigret (sacre bleu!) and Maigret and the Hundred Gibbets. Personally, I'd have been inclined to call it simply The Hanged Man, as the new title is a bit of a mouthful, but perhaps the shorter version didn't seem distinctive enough.

The version I read was the translation from 2014 by Linda Coverdale, published by Penguin. The translation struck me as exceptionally readable and gripping, and credit must go to Coverdale as well as to Simenon. In my youth, I found some of the translations of Simenon that I read rather drab, but the more recent ones that I've come across are more appealing. Perhaps, also, I've become more interested in Simenon as I've got older. Despite his huge popularity, he is, for some, an acquired taste.

In this book, Maigret is working in Belgium when he sees a poorly dressed man posting a large number of banknotes to an address in Paris. Intrigued, the detective follows the man and - extraordinarily but somehow characteristically - switches the suitcase the man is carrying for another. This crucial plot development, unlikely yet arresting, seems to me to typify Simenon.

The man discovers the switch and promptly commits suicide. Even Maigret's customary calm is slightly ruffled by this shocking development. So what was in the man's suitcase - a fortune in banknotes? No, an old, bloodstained suit. What on earth is going on?

As Maigret follows a strange trail, and risks his life on more than one occasion, he comes across an odd group of individuals linked together by past events. Like all the other Maigret novels I've read, this is a short, snappy book, and it's probably the Maigret that I've most enjoyed reading. Maigret's actions are sometimes improbable, but Simenon's gift is to make them seem psychologically plausible. The same goes for the behaviour of the other characters in this entertaining story.

The version I read was the translation from 2014 by Linda Coverdale, published by Penguin. The translation struck me as exceptionally readable and gripping, and credit must go to Coverdale as well as to Simenon. In my youth, I found some of the translations of Simenon that I read rather drab, but the more recent ones that I've come across are more appealing. Perhaps, also, I've become more interested in Simenon as I've got older. Despite his huge popularity, he is, for some, an acquired taste.

In this book, Maigret is working in Belgium when he sees a poorly dressed man posting a large number of banknotes to an address in Paris. Intrigued, the detective follows the man and - extraordinarily but somehow characteristically - switches the suitcase the man is carrying for another. This crucial plot development, unlikely yet arresting, seems to me to typify Simenon.

The man discovers the switch and promptly commits suicide. Even Maigret's customary calm is slightly ruffled by this shocking development. So what was in the man's suitcase - a fortune in banknotes? No, an old, bloodstained suit. What on earth is going on?

As Maigret follows a strange trail, and risks his life on more than one occasion, he comes across an odd group of individuals linked together by past events. Like all the other Maigret novels I've read, this is a short, snappy book, and it's probably the Maigret that I've most enjoyed reading. Maigret's actions are sometimes improbable, but Simenon's gift is to make them seem psychologically plausible. The same goes for the behaviour of the other characters in this entertaining story.

Wednesday, 22 August 2018

Back from Germany

I've been very busy writing lately, and I was certainly ready for a break from the keyboard. For most of my writing life, I've had to fit the writing in around my legal career; now, it's very much the other way round, and over a spell of about four weeks I must have chalked up a higher word count than in any comparable period as a writer. But of course writing needs to remain fresh at all times, and I was glad of the chance to spend five nights in Germany from which I've just returned.

This was a trip around some medieval centres which I knew little or nothing about, other than Heidelberg, which has long been on my wish list. And the combination of great weather, charming locations, and a very good guide in Frank Pattinson (who was perhaps the best of the many tour guides I've come across over the years) proved, if not precisely restful, at least an excellent way of recharging the batteries.

The first destination was Wurzburg, a town which boasts plenty of sights along the riverside. There's a formidable fortress on top of a hill which commands spectacular views of the old town, including a charming and historic old bridge, which reminded me of the bridge in Prague. Other stops in the area included Rothenburg - delightful, with an old city wall - and Bamberg, with an amazing old town hall built on an island in the river.

Heidelberg, naturally, was a highlight, a fantastic university town which offers river trips on a solar-powered catamaran: an absolute must if, like me, you love boat trips. The massive and picturesque old castle, reached either by funicular train or (a lot of) steps proved equally memorable. Of course, it's a place with a dark history, as a former Nazi stronghold, and there are poignant reminders of past horrors supplied by "stumbling stones" which are placed in the pavements in memory of Jewish people who died at the hands of the Nazis.

There were plenty of other places to visit as well, including a very charming and attractive town called Wertheim, and Mannheim's impressive botanical gardens, complete with pelicans and flamingoes.

All in all, this is a part of the world which I can strongly recommend to anyone looking for somewhere a bit different. For once, I didn't come away with a new idea for a short story, but I did plenty of thinking about my works-in-progress and the challenge now is to get them down in black and white! Oh, and I had the chance to read a number of excellent crime novels which will feature before long as Forgotten Books.

Tuesday, 21 August 2018

Copy-editing a Manuscript - Why does it matter?

A few weeks ago, I attended an enjoyable Society of Authors event in Harrogate. Among a number of interesting people whom I met for the first time was Louis Greenberg, the chap who copy-edited Gallows Court - a very pleasant surprise! All the more pleasant since I'd found his copy-editing very efficient indeed. And this matters, because it's really important to make sure that a book on which one has laboured long and hard doesn't falter at the last fence because of a lack of care in production. Yes, there will always be some things that slip through the net - regrettable, but that's life. However, a professional writer cares very much about trying to keep glitches to a minimum, and the reality is that one needs help on this, because so often the original author sees what he or she thinks should be on the page - not what is actually there!

On discovering that Louis is himself an author as well as an editor I suggested that he contribute a guest post about the art of editing. He kindly obliged - and here's the result:

https://louisgreenberg.com/etc.html"

On discovering that Louis is himself an author as well as an editor I suggested that he contribute a guest post about the art of editing. He kindly obliged - and here's the result:

"When Head of Zeus asked me to copy-edit

Martin Edwards’ Gallows Court, I

jumped at the chance. It’s an enticing mystery set in 1930 London and I felt

transported into the fog and freeze of that dark winter and the intricate and

compelling murder plot that plays out there. But at the same time, I suspected

that it would be a challenge – to find something to correct.

Copy-editing is a fine-tooth, stickling

business, a different mental process from the creative splurge of drafting

fresh fiction. Even writers who can edit will struggle to inhabit both

headspaces on the same project. As an author myself, I think of myself as

author’s editor, sensitive to retaining the writer’s voice, wisdom and

intentions. I like to treat my clients’ manuscripts with the respectful care

and attention I hope will be given to my own work.

Even when copy is very clean, each book

throws up its own themes: in one job I’ll find myself revisiting everything I

knew about the use of the appositive compound modifier; in another, pondering

the semantic philosophy behind serial commas.

I’ve written marginal opinion

pieces about the spelling of whisky, the naturalisation of corporate

neologisms, the most efficient rendering of non-standard gangster slang, and the

language-rotting tendency to forget plurals when on safari. I’ve contributed to

house style guides on italicisation of non-English terms and consulted

manufacturers’ guides on the correct typography of HK VP9s, RAP-401s and GTIs –

then broken those rules when the author has a consistent, deliberate case.

Still, when it came to Gallows Court, I knew I’d struggle. Martin

is such a vastly experienced novelist and, as suspected, the plot was seamlessly

rendered and the research meticulous. I get a hit of nerdish serotonin when I’m

editing a historical novel and catch an anachronism before it gets to print,

but Gallows Court only offered me only

one, very marginal, case. In the end all I could offer Martin was some

nitpicking on honorific capitalisation and hyphenated compounds. I’m glad he

didn’t find it unbearably irritating and still invited me to write this post!

Friday, 17 August 2018

Forgotten Book - His Name Was Death

Fredric Brown was a highly distinctive American writer, as well known for his science fiction as for his work in the mystery field. He wrote superb short stories, including one of my all-time favourites, "Don't Look Behind You", which illustrates his inventiveness of thought as well as his flair for plotting. I first came across his novels when the excellent Zomba Books imprint published an omnibus of four of them, with an intro by Harry Keating, and I've admired his work ever since.

His Name Was Death is a characteristically clever story with one of the arresting openings that Brown favoured: "Her name was Joyce Dugan, and at four o'clock on this February afternoon she had no remote thought that within the hour before closing time she was about to commit an act that would instigate a chain of murders". She's working in a print shop, and a young man whom she knew a few years ago comes in to collect some money that her boss owes. It all seems very straightforward, and they even make a date...

Brown makes good use in this novel of multiple viewpoints. Some of them belong to the same person, who adopts a number of different identities; don't worry, this isn't a spoiler! Events move quickly and disastrously as one crime leads inexorably to another. There is also a fascinating portrayal of a person whose determination to commit the perfect crime is hampered by a sequence of unfortunate events.

First published in 1954, this is a gripping and highly readable book. Wisely, Brown kept it short, but it's definitely not an expanded short story: it's a nicely plotted novel with sharp characterisation and a highly satisfactory finale. I'm a Fredric Brown fan, and I can recommend not only this book but other titles such as The Screaming Mimi and Night of the Jabberwock. And how can you not love an author who once wrote a story titled "Paradox Lost"?

His Name Was Death is a characteristically clever story with one of the arresting openings that Brown favoured: "Her name was Joyce Dugan, and at four o'clock on this February afternoon she had no remote thought that within the hour before closing time she was about to commit an act that would instigate a chain of murders". She's working in a print shop, and a young man whom she knew a few years ago comes in to collect some money that her boss owes. It all seems very straightforward, and they even make a date...

Brown makes good use in this novel of multiple viewpoints. Some of them belong to the same person, who adopts a number of different identities; don't worry, this isn't a spoiler! Events move quickly and disastrously as one crime leads inexorably to another. There is also a fascinating portrayal of a person whose determination to commit the perfect crime is hampered by a sequence of unfortunate events.

First published in 1954, this is a gripping and highly readable book. Wisely, Brown kept it short, but it's definitely not an expanded short story: it's a nicely plotted novel with sharp characterisation and a highly satisfactory finale. I'm a Fredric Brown fan, and I can recommend not only this book but other titles such as The Screaming Mimi and Night of the Jabberwock. And how can you not love an author who once wrote a story titled "Paradox Lost"?

Monday, 13 August 2018

Gallows Court

Receiving an advance copy of one's latest book is always exciting, and the arrival of a first copy of Gallows Court is a very special moment for me. Partly because I worked on it for such a long time, mostly for the connected reason that it's such a departure for me as a crime writer.

Head of Zeus have worked tirelessly on the jacket artwork. This is always an important part of the process, and I've been hugely impressed by the attention they've given to it. A wide range of designs were considered in the search for something that captured the flavour of a 1930s thriller, and I'm really pleased with the outcome of their efforts.

I've talked to Crime Time about the book; my thanks to them for commissioning the interview. And I'm thrilled by the reaction of a number of leading authors who read the book at proof stage. More about what they've had to say on another occasion.

It's all very exciting, and Head of Zeus have kindly arranged a launch in central London on 18 September which should be great fun. If any readers are interested in attending, let me know either by email or by commenting on this post and I'll see if an invitation can be sorted out.

Saturday, 11 August 2018

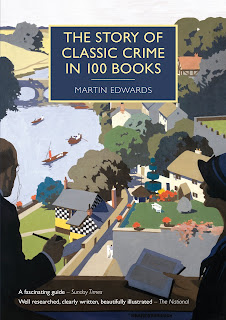

The Story of Classic Crime in paperback

The Story of Classic Crime in 100 Books has just been published in paperback, another stage in the story of a book which has itself become a personal favourite of mine. Like The Golden Age of Murder, it's been a very lucky book for me. What started out as an idea to write a straightforward sort of companion to the British Library's Crime Classics series turned into something rather more ambitious.

It's in the nature of writing that, when you get to work, you find that you go in directions not necessarily contemplated when you first drew up a synopsis for a publisher, or first had your bright idea to create something new. With this book, I found myself telling a story of the evolution of the genre in the first half of the last century, a period of remarkable development. The books I chose (and in my enthusiasm, I did sneak over the 100 mark!) told part of that story, but so did the detailed intros to each of the chapters, which sought to set individual titles in context.

With all books, you never really know how the majority of people are going to react until it's too late. Will they "get" what you're trying to do? It's far from certain. This time, though, the reaction has been hugely gratifying. Only the other day, there was a wonderful review on the Random Jottings blog which truly delighted me. "Prepare to be beguiled" is a lovely phrase to link to a work of non-fiction...

The icing on the cake is that this year has seen the book nominated for five awards, three in the US (Agatha, Anthony, and Macavity) and two in the UK (Gold Dagger for non-fiction and HRF Keating). This sort of thing doesn't happen very often in an author's life, if at all, and it's another reason why it's been such a lucky book. I'm hoping, too, that the paperback edition will find a further readership. And perhaps that some of those who enjoy the book will be tempted to see what I've made of the Golden Age thriller in Gallows Court!

It's in the nature of writing that, when you get to work, you find that you go in directions not necessarily contemplated when you first drew up a synopsis for a publisher, or first had your bright idea to create something new. With this book, I found myself telling a story of the evolution of the genre in the first half of the last century, a period of remarkable development. The books I chose (and in my enthusiasm, I did sneak over the 100 mark!) told part of that story, but so did the detailed intros to each of the chapters, which sought to set individual titles in context.

With all books, you never really know how the majority of people are going to react until it's too late. Will they "get" what you're trying to do? It's far from certain. This time, though, the reaction has been hugely gratifying. Only the other day, there was a wonderful review on the Random Jottings blog which truly delighted me. "Prepare to be beguiled" is a lovely phrase to link to a work of non-fiction...

The icing on the cake is that this year has seen the book nominated for five awards, three in the US (Agatha, Anthony, and Macavity) and two in the UK (Gold Dagger for non-fiction and HRF Keating). This sort of thing doesn't happen very often in an author's life, if at all, and it's another reason why it's been such a lucky book. I'm hoping, too, that the paperback edition will find a further readership. And perhaps that some of those who enjoy the book will be tempted to see what I've made of the Golden Age thriller in Gallows Court!

Friday, 10 August 2018

Forgotten Book - Mirror, Mirror, on the Wall

Mirror, Mirror on the Wall is a novel which illustrates, among other things, the late Stanley Ellin's versatility as a crime writer. He was always, and will I think remain, best known as an author of short stories, most famously "The Specialty of the House", but he was also an accomplished novelist, equally at ease with the private eye story and with the novel of psychological suspense.

The first edition dust jacket of Mirror, Mirror, describes the book as "spellbinding, shocking - unlike anything else Stanley Ellin has ever written". The victim of the bullet lies on Peter Hibben's bathroom floor in his Greenwich Village apartment. What has happened? The scene seems like a nightmare, yet it is not. Peter's search for answers becomes a journey into his sexual past". The blurb concludes: "The disclosures will be disturbing to some, but you will not be able to put Mirror, Mirror down any more than you can guess the outcome".

The book was first published in 1972, and the date is significant. At the time, the publication of Portnoy's Complaint had ushered in a new era of frankness about sex; it's impossible to imagine this book being regarded as publishable even ten years earlier, even though the central plot twist was comparable to that in an earlier classic of psychological suspense (no, I'm not going to reveal which one!) I suspect that present day readers may feel that Ellin takes the then-new freedoms a bit too far at times, but it's certainly true that he manages to blend controversial material with a plot of classic ingenuity. The story is, in essence, a cunning refashioning of the "whowasdunin" type of mystery, and there is even a sort of cipher which provides a vital clue to the mystery.

Harry Keating included this novel in his list of the 100 best crime books; it also won a major prize in France. Keating pointed out, correctly, that as well as all the shocking stuff, there's plenty of humour. This was, in its day, a ground-breaking crime novel, and although I have some reservations about it, it is nevertheless a good example of the taut, readable prose of an author who was in the front rank of post-war American mystery writers, and deserves to be remembered.

The first edition dust jacket of Mirror, Mirror, describes the book as "spellbinding, shocking - unlike anything else Stanley Ellin has ever written". The victim of the bullet lies on Peter Hibben's bathroom floor in his Greenwich Village apartment. What has happened? The scene seems like a nightmare, yet it is not. Peter's search for answers becomes a journey into his sexual past". The blurb concludes: "The disclosures will be disturbing to some, but you will not be able to put Mirror, Mirror down any more than you can guess the outcome".

The book was first published in 1972, and the date is significant. At the time, the publication of Portnoy's Complaint had ushered in a new era of frankness about sex; it's impossible to imagine this book being regarded as publishable even ten years earlier, even though the central plot twist was comparable to that in an earlier classic of psychological suspense (no, I'm not going to reveal which one!) I suspect that present day readers may feel that Ellin takes the then-new freedoms a bit too far at times, but it's certainly true that he manages to blend controversial material with a plot of classic ingenuity. The story is, in essence, a cunning refashioning of the "whowasdunin" type of mystery, and there is even a sort of cipher which provides a vital clue to the mystery.

Harry Keating included this novel in his list of the 100 best crime books; it also won a major prize in France. Keating pointed out, correctly, that as well as all the shocking stuff, there's plenty of humour. This was, in its day, a ground-breaking crime novel, and although I have some reservations about it, it is nevertheless a good example of the taut, readable prose of an author who was in the front rank of post-war American mystery writers, and deserves to be remembered.

Tuesday, 7 August 2018

Great News for Locked Room Fans

On this blog and elsewhere, I've mentioned many times that one of my absolute favourite books about the crime genre is the late Bob Adey's marvellous and unique Locked Room Murders. Bob was a great guy, to whom I dedicated Miraculous Mysteries, and from whose widow Sue I've been able to acquire a number of gems for my own collection. I'm the proud possessor of copies of the first and second editions which Bob inscribed for me years ago, but for a long time it's been a source of frustration and regret that other fans have been unable to track down copies at affordable prices.

Now that's going to be put right. I'm delighted to hear from John Pugmire that the book is to reappear, under his Locked Room International imprint. And even better news, an update is in the works. Here is the information John has passed on to me:

"Locked Room Murders is a bibliography

containing a description of the problem and, separately, the solution to locked

room and impossible crime novels and short stories.

It has been a classic in the locked room

pantheon for over 40 years, beginning with a 1972 article by Bob Adey in The Armchair Detective. The first

edition of Locked Room Murders,

published by Ferret Fantasy in 1979, covered 1280 titles. The 1991 second edition, published by Crossover Press, covered 2019 titles.

Due to limited print runs, both editions

have become prohibitively expensive. Locked Room International (LRI) is now making

a revised version of the Second Edition available at an affordable price.

Edited by Brian Skupin, LRI consultant and co-publisher of Mystery Scene magazine, this revised version contains the same 2019

titles, but with corrections and additional references which have appeared

since 1991.

Plans are in place to publish a Supplemental

Edition in 2019, to include novels and short stories (including translations from

sources outside the Anglosphere) published since 1991, films, TV series, graphic

novels, and other media. It will not contain any of the titles in the Second

Edition, Revised."

Monday, 6 August 2018

The Dorothy L. Sayers Society Annual Conference

I had a fleeting trip to Lancaster this week-end, to the Dorothy L. Sayers Society's Annual Conference. I've been a member of the Society for quite some time, and six years ago, gave their Annual Lecture at Witham in Essex, on the subject of DLS' true crime writing. More recently I worked with them on the publication of Sayers' collected crime reviews, for which I wrote a long commentary: Taking Detective Stories Seriously is a book I'm rather proud to be associated with. This time, I'd been invited to be guest of honour at the conference banquet on Saturday evening.

When the invitation first arrived, my plan was to make the most of the trip by attending the whole conference. Writing commitments made that impossible, alas; a real shame because it was clear from what I heard while I was there that delegates had been treated to several fascinating talks. The venue, incidentally, was Lancaster University, and I was intrigued by the campus, the geography of which seems to a stranger to be rather Kafkaesque. Bemused, I stopped at a map at one point, to be joined by a taxi driver, who said, "I've been coming here thirty years, mate,and I still get lost."

Anyway, I eventually found my way around, and met up with the Society members. The banquet was really enjoyable, and I was especially interested to meet someone who once corresponded with Paul McGuire, a relatively obscure but highly capable Australian detective novelist of the Golden Age, whom Sayers - among others - reviewed warmly. And once I'd given my speech at the conclusion of the banquet, I was able to relax over a drink or two. All very agreeable.

The Society does a great job in engaging with Sayers fans all around the world, and is well worth joining if you're a fan. My thanks to Seona Ford, Chair of the Society, for making my trip such an enjoyable one.

When the invitation first arrived, my plan was to make the most of the trip by attending the whole conference. Writing commitments made that impossible, alas; a real shame because it was clear from what I heard while I was there that delegates had been treated to several fascinating talks. The venue, incidentally, was Lancaster University, and I was intrigued by the campus, the geography of which seems to a stranger to be rather Kafkaesque. Bemused, I stopped at a map at one point, to be joined by a taxi driver, who said, "I've been coming here thirty years, mate,and I still get lost."

Anyway, I eventually found my way around, and met up with the Society members. The banquet was really enjoyable, and I was especially interested to meet someone who once corresponded with Paul McGuire, a relatively obscure but highly capable Australian detective novelist of the Golden Age, whom Sayers - among others - reviewed warmly. And once I'd given my speech at the conclusion of the banquet, I was able to relax over a drink or two. All very agreeable.

The Society does a great job in engaging with Sayers fans all around the world, and is well worth joining if you're a fan. My thanks to Seona Ford, Chair of the Society, for making my trip such an enjoyable one.

Friday, 3 August 2018

Forgotten Book - The Greek Coffin Mystery

Ellery Queen's name lives on today mainly through the wonderful mystery magazine which bears his name, and I suspect that there are plenty of modern readers who are unfamiliar with the Ellery Queen novels. Yet the books written by Ellery Queen (a pen-name for two cousins) and starring a young and brilliant amateur detective whose father was, conveniently, a cop, made a huge impact during the Golden Age, and for decades afterwards. It's interesting, however, that when I give talks about Golden Age fiction, I'm sometimes asked if there were any American counterparts to Christie, Sayers, and company. Mention of Ellery Queen's name is often greeted by blank faces.

The Greek Coffin Mystery, first published in 1932, was the fourth Queen novel, and is widely regarded by connoisseurs of Golden Age fiction as a classic example of the cerebral whodunit. There is a cast of characters - 33 of them, plus six staff detectives, are named. There is a foreword, explaining that this case occurred very early in Ellery's sleuthing career. There's a map of the location of the main action. There are two floor plans. There is a jaunty "challenge to the reader". There are no fewer than four elaborate solutions to the mystery put forward at various times. And there is a contents list which reveals that the initial letters of the chapter titles form an acrostic, giving the title of the book and name of the author. What more could any Golden Age fan want?

A elderly, blind Greek art dealer and collector dies of heart failure at his residence in New York. But was he blind? Did he die of natural causes? These questions spring instantly to mind, but aren't really central to the mystery. A missing will - another classic Golden Age ingredient - certainly is, and so is the discovery of the body of someone who is undoubtedly a murder victim.

The plot twists and turns, and it almost goes without saying that it's very cleverly constructed. That long list of characters is a clue to one of the story's flaws - there are so many people in it that it's not entirely easy to keep them all straight in one's mind, and it's certainly impossible to care about the fate of most of them. And I do find the early Ellery a bit wearisome - he became more human and, to my mind, more appealing in later books. But if it's an ingenious plot you're after, this novel certainly delivers.

The Greek Coffin Mystery, first published in 1932, was the fourth Queen novel, and is widely regarded by connoisseurs of Golden Age fiction as a classic example of the cerebral whodunit. There is a cast of characters - 33 of them, plus six staff detectives, are named. There is a foreword, explaining that this case occurred very early in Ellery's sleuthing career. There's a map of the location of the main action. There are two floor plans. There is a jaunty "challenge to the reader". There are no fewer than four elaborate solutions to the mystery put forward at various times. And there is a contents list which reveals that the initial letters of the chapter titles form an acrostic, giving the title of the book and name of the author. What more could any Golden Age fan want?

A elderly, blind Greek art dealer and collector dies of heart failure at his residence in New York. But was he blind? Did he die of natural causes? These questions spring instantly to mind, but aren't really central to the mystery. A missing will - another classic Golden Age ingredient - certainly is, and so is the discovery of the body of someone who is undoubtedly a murder victim.

The plot twists and turns, and it almost goes without saying that it's very cleverly constructed. That long list of characters is a clue to one of the story's flaws - there are so many people in it that it's not entirely easy to keep them all straight in one's mind, and it's certainly impossible to care about the fate of most of them. And I do find the early Ellery a bit wearisome - he became more human and, to my mind, more appealing in later books. But if it's an ingenious plot you're after, this novel certainly delivers.

Wednesday, 1 August 2018

Francis Durbridge: the Complete Guide

One of the pleasures for me of June's Bodies from the Library event was the chance to meet Melvyn Barnes. I first came across his work when I read his Best Detective Fiction, and then its subsequent incarnation, Murder in Print. We've corresponded for some years, but this was our first meeting in person. He was at the British Library to speak about Francis Durbridge, an author on whom he is our leading authority, and about whom he's written a book.

This is Francis Durbridge: the Complete Guide. In fact, it's an updated and significantly expanded version of his Francis Durbridge: a Centenary Appreciation. That book was self-published; this one appears under the imprint of a worthy independent press, Williams and Whiting. I enjoyed the earlier book, but the new version does offer much more, and is definitely worth buying even if you invested in its predecessor.

A brief biographical chapter is followed by a lengthy survey of Durbridge's career. Then come sections on his novels, his work for radio (there was a lot of it), his work for television (which is how I first came across his name in my youth), his stage plays, films of his stories, and (yes!) the Paul Temple comic strip.

One of the valuable features of the book is that it disentangles the numerous overlapping strands of Durbridge's output. He was prolific, sure, but he also re-used the same plots on many occasions. This can be confusing and indeed irritating, so it's helpful to be able to find out, for instance, that Design for Murder is actually a novelisation of the radio serial Paul Temple and the Gregory Affair, while Paul Temple and the Alex Affair is actually a revision of the earlier Send for Paul Temple Again. This is a book I shall refer to time and again, and it's a must for any serious Durbridge fan; a bonus is an intro by Nicholas Durbridge. I should declare that I'm mentioned in the acknowledgements, but that's immaterial - I'd recommend this book anyway.

This is Francis Durbridge: the Complete Guide. In fact, it's an updated and significantly expanded version of his Francis Durbridge: a Centenary Appreciation. That book was self-published; this one appears under the imprint of a worthy independent press, Williams and Whiting. I enjoyed the earlier book, but the new version does offer much more, and is definitely worth buying even if you invested in its predecessor.

A brief biographical chapter is followed by a lengthy survey of Durbridge's career. Then come sections on his novels, his work for radio (there was a lot of it), his work for television (which is how I first came across his name in my youth), his stage plays, films of his stories, and (yes!) the Paul Temple comic strip.

One of the valuable features of the book is that it disentangles the numerous overlapping strands of Durbridge's output. He was prolific, sure, but he also re-used the same plots on many occasions. This can be confusing and indeed irritating, so it's helpful to be able to find out, for instance, that Design for Murder is actually a novelisation of the radio serial Paul Temple and the Gregory Affair, while Paul Temple and the Alex Affair is actually a revision of the earlier Send for Paul Temple Again. This is a book I shall refer to time and again, and it's a must for any serious Durbridge fan; a bonus is an intro by Nicholas Durbridge. I should declare that I'm mentioned in the acknowledgements, but that's immaterial - I'd recommend this book anyway.