It's a long time since I read Alec Coppel's novel Mr Denning Drives North, but I remembered it as a decent suspense story, and this prompted me to watch the film version, made in 1951, a couple of years after the book appeared. Coppel was a capable writer, with a particular gift for dialogue and building tension. He was one of the writers of Vertigo, one of the finest of all crime films - some would say the finest.

The protagonist is played by John Mills, who as ever is a thoroughly decent Englishman. He's well off, happily married, and has an attractive daughter. But at the start of the film, he's plagued by nightmares, and it appears that he has a guilty conscience. It's soon clear that he's implicated in a murder case, and before long he confesses the truth to his wife, played by Phyllis Calvert.

His daughter had fallen for a loathsome chap, played by Herbert Lom, and Denning wanted to buy off the blackguard. He persuades him to write a letter breaking off the relationship, on payment of £500, but when he feels that his daughter's honour is insulted, he hits the chap, who falls on the hearth and dies. Manslaughter rather than murder, I'd have thought, but our hero makes the first of several extremely foolish decisions when he decides to cover up the crime.

He doesn't actually drive all that far north to dispose of the corpse; the southern reaches of the Home Counties, by the look of things. But the plot thickens when the body disappears. Denning continues to behave so foolishly that I found it rather difficult to root for him, but I did admire the way in which Coppel piled on the complications. It's a crafty story, and the film benefits from a good cast, with Wilfred Hyde White especially entertaining as a mortuary attendant. Bernard Lee plays a good natured cop, and Sam Wanamaker is a young American patents lawyer who falls for Denning's daughter and unwittingly does his utmost to bring Denning's crime to the attention of the authorities. It's pretty good entertainment.

Tuesday, 30 April 2019

Monday, 29 April 2019

Body Heat - 1981 film

Over the years, I've mentioned Lawrence Kasdan's 1981 film Body Heat numerous times on this blog, but I've never discussed it in much detail. Time to put that right, because it is, quite simply, my favourite crime film. I first saw it at the cinema in Leicester Square shortly after its release. I was impressed, and despite knowing what happens, I've enjoyed watching it several times since.

Body Heat is in the tradition of that great film (and book) Double Indemnity. That is, it's the story of a charming but weak man who falls for a femme fatale with an inconvenient husband. Some critics have taken the view that Body Heat is a mere act of homage, but although I am a great admirer of Double Indemnity, I think that Kasdan takes the central idea and theme and makes a truly distinctive film of his own, a film of real and lasting quality.

Everything about it is right. There isn't a wasted word in the script, and the film is visually alluring, with the oppressive heat of Florida's coast captured tellingly. And the brilliant score by John Barry is superbly atmospheric. Barry won five Oscars and also composed the definitive James Bond soundtracks, but I don't think this gifted musician did anything much better than Body Heat.

And then there is the acting. William Hurt is fantastic as the likeable but sleazy lawyer Ned Racine, whose incompetence at his job plays a crucial part in the very clever plot. Kathleen Turner made her name in this film, and although some critics have been rather dismissive of her acting skills, I think she gives a terrifically well-judged performance. You can really believe in Ned's obsession about her. The supporting cast, including Mickey Rourke, Ted Danson, and J.A. Preston, is exceptionally good.

What's not to like? If you're a crime fan, and you haven't seen Body Heat, you really do have a treat in store.

Friday, 26 April 2019

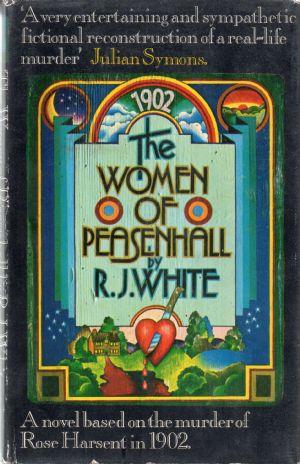

Forgotten Book - The Women of Peasenhall

A remarkable number of crime novels have been based, directly or indirectly, on real life criminal cases, and The Women of Peasenhall by R.J. White is an example. The novel was published by Macmillan in 1969, and earned high praise (emblazoned on the front cover) from Julian Symons, no less. The book was White's second to be based on a true crime. His prize-winning The Smartest Grave, published eight years earlier, was inspired by the Moat Farm Murder, and introduced the rather likeable Inspector Brock, who returns here.

Reginald James White came to crime writing late in life, and this book appeared only a couple of years before his death. He was a Fellow of Downing College, Cambridge, and his subject was history. He published several well-regarded history books, and his erudition is certainly on display here. Mind you, there is one howler - Brock's wife refers to the actress Gladys Cooper, whose acting career did not begin until a few years after the events of the story. Ooops. But it's reassuring, I tend to think, to see that even the most learned authors can get things wrong - as we all do from time to time.

The book is based on the unsolved murder of Rose Harsent in a remote Suffolk village in 1902. The case is something of a classic. The same man, William Gardiner, was tried for the murder twice, but not convicted, and lived for almost another forty years. White captures the strange village atmosphere pretty well, I think, and introduces us to the word "proxymater" - which means a woman who has sex with a man to keep him happy while his wife is pregnant; we are a long way from contemporary mores here.

White comes up with an intriguing explanation of the crime, but the book is a rather odd one, elliptically told, and one gift he did not have was that of building tension and suspense. It's a short book, but still moves rather slowly. A lesbian sub-plot is never developed, and we don't get a real sense of the victim's personality, while the female character who clearly interests White the most is sketched in a rather incomplete way. White managed to interest me in the Peasenhall puzzle and I liked his book but felt he could have improved it by working on it more.

Wednesday, 24 April 2019

The End of an Era

My spell as Chair of the Crime Writers' Association was one I found fascinating and enjoyable, though inevitably it did take up a lot of time. But it gave me deeper insight into the workings of the crime writing world and also the issues facing crime writers at a time of much change in the publishing industry. I've been a member of the CWA for more than 30 years, and I've gained a great deal from my membership. So trying to build on the work of my predecessors also afforded an opportunity to give something back. As well as the chance of consuming the occasional CWA cupcake...

I'm not a natural "committee" person, and I've always been aware that committees are not always effective; in my working life I've also come across many disputes in voluntary and not-for-profit bodies. However, I did find that my apprenticeship as a member of the CWA committee, or board of directors, to be more accurate, under the chairmanship of Peter James, Alison Joseph, and Len Tyler, was very helpful in enabling me to get a clearer understanding of the way the organisation works, and of its potential.

My over-riding aim was to build on the fact that the membership of the CWA has been growing impressively for a number of years, and help to refashion the infrastructure of the organisation. A lot of this sort of thing is unglamorous - sorting out the finances, updating the legal constitution, managing the paid agencies who carry out various projects- but essential. My message to members was that we had to be business-like, because that was the only way to ensure that a large and growing organisation could serve its members effectively. Avoiding increases in member subscriptions while developing an ever wider range of member benefits seemed to me to be crucial. And also, one has to get across the message about those benefits, and to communicate effectively with people who read, or might want to read, members' books.

So rather than having numerous lengthy board meetings (my experience of partners' meetings in a law firm has irrevocably turned me off the idea of long meetings and endless going round in circles) I tried to develop a way of working in which a wide and expanding range of individuals undertook specific projects, with sound admin and financial management in the background. So the CWA now has, among other things, three Libraries Champions, two Festival Liaison Officers, a Booksellers' Champion, a Publishers' Liaison Officer, and a number of other people doing invaluable work of various kinds - I'm especially proud of the work we've started on supporting writers who face mental health challenges.

The Board members, and the admirable Secretary Dea Parkin, proved wonderfully supportive, and the way they dealt with the occasional tricky issue which arose was a model of sensible and constructive conduct. I was also delighted by the way the membership as a whole reacted, understanding the need to make changes while retaining the ethos that has made the CWA so cohesive over the past 65 years.

Of course, there are some things which I'd like to have done which I never quite managed, not least visiting each of the regional CWA chapters (though I did get to several of them), but I'm delighted that my elected successor is Linda Stratmann, someone who will bring her own ideas and energy to benefit an organisation which does seem to me to be going from strength to strength. I've handed over to her, as is the custom, the Creasey Bell (see top photo) which has resided in my house since early 2017, and I wish her all the very best.

As it turns out, I'm the only person who has served as CWA Chair and Detection Club President at the same time, and I also became the longest-serving Chair of the CWA since our founder, John Creasey, back in the 1950s. So it's definitely time to step aside and get some more writing done. But I'm going to continue to be involved with the CWA, not least as anthologist and archivist. And I'm very glad to belong to such a thriving and forward-looking organisation.

Bonnie and Clyde - 1967 film review

I'm more than half a century late, which even by my standards is exceptionally tardy, but I've finally got round to watching Bonnie and Clyde, the highly successful movie starring Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway which (among other things) inspired a song by Georgie Fame. The director was Arthur Penn, whom I know best as director of a rather good crime film, Night Moves.

It was a historical film, set in 1934, and it's a tale of two outlaws. There are some similarities to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, which came along soon afterwards, although the latter is more of a comedy, and has a superior soundtrack. Clyde Barrow (Beatty), recently released from prison, picks up an attractive young waitress (Dunaway), who is fascinated by his looks and his refusal to conform to society's norms.

Patricia Highsmith famously argued that such characters are dramatically interesting because they have a kind of freedom in the way they behave (I'm paraphrasing), and although I don't entirely buy into this argument, I can see its force. The trouble is that the likes of Bonnie and Clyde are essentially doomed figures. They are really not very bright, and neither is their hapless sidekick C.W. Moss (Michael J. Pollard). They also team up with Clyde's brother Buck (Gene Hackman) and his wife Blanche (Estelle Parsons). The stellar cast also includes Gene Wilder.

It's a film that doesn't shy away from violence, and it was shocking in its day. Some saw it as glorifying violence, and historical accuracy certainly is not a strong point. But it was enormously successful and influential. I found it very watchable, and the relationship between the impotent Clyde and Bonnie is cleverly presented. Does it glorify violence? On balance, I'd argue that it doesn't, because you'd have to be very stupid indeed to see someone as brainless as Clyde as a role model. I suppose the counter-argument is that people with a propensity to violence are often very stupid, and crime should not be made to seem attractive. But you only have to consider what happens to the criminals in this film to see that there's nothing attractive about dying young and painfully.

It was a historical film, set in 1934, and it's a tale of two outlaws. There are some similarities to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, which came along soon afterwards, although the latter is more of a comedy, and has a superior soundtrack. Clyde Barrow (Beatty), recently released from prison, picks up an attractive young waitress (Dunaway), who is fascinated by his looks and his refusal to conform to society's norms.

Patricia Highsmith famously argued that such characters are dramatically interesting because they have a kind of freedom in the way they behave (I'm paraphrasing), and although I don't entirely buy into this argument, I can see its force. The trouble is that the likes of Bonnie and Clyde are essentially doomed figures. They are really not very bright, and neither is their hapless sidekick C.W. Moss (Michael J. Pollard). They also team up with Clyde's brother Buck (Gene Hackman) and his wife Blanche (Estelle Parsons). The stellar cast also includes Gene Wilder.

It's a film that doesn't shy away from violence, and it was shocking in its day. Some saw it as glorifying violence, and historical accuracy certainly is not a strong point. But it was enormously successful and influential. I found it very watchable, and the relationship between the impotent Clyde and Bonnie is cleverly presented. Does it glorify violence? On balance, I'd argue that it doesn't, because you'd have to be very stupid indeed to see someone as brainless as Clyde as a role model. I suppose the counter-argument is that people with a propensity to violence are often very stupid, and crime should not be made to seem attractive. But you only have to consider what happens to the criminals in this film to see that there's nothing attractive about dying young and painfully.

Friday, 19 April 2019

Forgotten Book - Deadly Picnic

John Bingham was in his early 70s, yet commendably trying for a fresh direction in his writing, when he published Deadly Picnic in 1980. Michael Jago's excellent biography of Bingham, The Man Who Was George Smiley, suggests that Bingham was trying to follow in the footsteps of Colin Dexter with this one, although his detective duo, King and Owen, were about as different from Morse and Lewis as could be imagined.

At the start of the book, King and Owen are getting on like a house on fire, and Owen seems set to replace King when he retires. But at a picnic with their wives, Owen is offended by King's wife Laura, and an estrangement develops. King learns that Owen isn't going to get his job, and steps down from the Met at once, improbably taking a job with a marriage bureau. We then learn, perhaps even more unexpectedly, that Owen has a drug habit.

King is concerned that a criminal called Buller is determined to exact revenge after being sent to prison. And it just so happens that Buller is threatening the woman who set up the marriage bureau. King soon concludes that he needs to kill Buller, who is admittedly a nasty piece of work. So he tries to plan the perfect murder.

Of course, things don't work out as expected. But long before the sadly foreseeable twist ending, the reader has ceased to care. Jago described this book as a "disaster", which killed Bingham's relationship with his then publishers, Macmillan. It's certainly an unsatisfactory piece of work, which seems to have been written in an increasingly perfunctory fashion. I'm afraid that the characters didn't ring true, and the plot didn't appeal to me. I like Bingham as a writer, and feel that he is seriously under-estimated nowadays, but alas, this book is the work of a man whose powers were in sad decline.

At the start of the book, King and Owen are getting on like a house on fire, and Owen seems set to replace King when he retires. But at a picnic with their wives, Owen is offended by King's wife Laura, and an estrangement develops. King learns that Owen isn't going to get his job, and steps down from the Met at once, improbably taking a job with a marriage bureau. We then learn, perhaps even more unexpectedly, that Owen has a drug habit.

King is concerned that a criminal called Buller is determined to exact revenge after being sent to prison. And it just so happens that Buller is threatening the woman who set up the marriage bureau. King soon concludes that he needs to kill Buller, who is admittedly a nasty piece of work. So he tries to plan the perfect murder.

Of course, things don't work out as expected. But long before the sadly foreseeable twist ending, the reader has ceased to care. Jago described this book as a "disaster", which killed Bingham's relationship with his then publishers, Macmillan. It's certainly an unsatisfactory piece of work, which seems to have been written in an increasingly perfunctory fashion. I'm afraid that the characters didn't ring true, and the plot didn't appeal to me. I like Bingham as a writer, and feel that he is seriously under-estimated nowadays, but alas, this book is the work of a man whose powers were in sad decline.

Forgotten Book- The Strange Blue Yawl

Lucille Fletcher's The Strange Blue Yawl, first published in 1964, is an instructive example of the novel of domestic suspense, and of the author's clever use of writing technique as a means of ratcheting up tension. It's not by any means my favourite of her books, but for any would-be writer wanting to study the craft, it would be well worth reading. The author set herself a very difficult challenge here, and I enjoyed seeing the way in which she tried to rise to it.

The story is a first person narrative. The decision to tell the tale in this way was unusual for Fletcher, but necessary to make the required impact, for a couple of reasons. Our narrator is John Waldo Leeds the Second, a 38 year old musician devoted to composition. He lives in a remote cottage near the mouth of the Chesapeake with his gorgeous young wife Mary, a former TV weather girl.

One night, Mary wakes him. She's heard a woman screaming from a boat in the bay. Groggily, Jack Leeds gets up and looks out. Mary has seen a blue yawl in the water, and is convinced that murder has been done. The couple aren't able to do anything else that night, but then Mary (rather belatedly, I thought) says she'll ring the Coast Guard. In the morning they are duly visited by a Lieutenant Reynolds, who proves to be far from helpful.

Mary convinces her husband that they are in danger and that the killers will seek them out unless they are apprehended first. She sets about some extensive amateur sleuthing and reports back on progress - but it appears that there are several suspicious yawls in the area, and even more dubious characters. The tension builds up to a dramatic climax and a rather extraordinary murder.

It's all very ingenious. However, I have to say that although Fletcher came up with a clever plot, she tested my ability to suspend disbelief to breaking point. I found the Leeds' behaviour odd and unconvincing, and the reports of the various suspects didn't hold my interest as it should have done. I wasn't convinced about the psychology of the characters, and in a novel of psychological suspense, that's quite a drawback. Even so, Fletcher was a dab hand at keeping you guessing, and for that reason, this story is worth reading.

The story is a first person narrative. The decision to tell the tale in this way was unusual for Fletcher, but necessary to make the required impact, for a couple of reasons. Our narrator is John Waldo Leeds the Second, a 38 year old musician devoted to composition. He lives in a remote cottage near the mouth of the Chesapeake with his gorgeous young wife Mary, a former TV weather girl.

One night, Mary wakes him. She's heard a woman screaming from a boat in the bay. Groggily, Jack Leeds gets up and looks out. Mary has seen a blue yawl in the water, and is convinced that murder has been done. The couple aren't able to do anything else that night, but then Mary (rather belatedly, I thought) says she'll ring the Coast Guard. In the morning they are duly visited by a Lieutenant Reynolds, who proves to be far from helpful.

Mary convinces her husband that they are in danger and that the killers will seek them out unless they are apprehended first. She sets about some extensive amateur sleuthing and reports back on progress - but it appears that there are several suspicious yawls in the area, and even more dubious characters. The tension builds up to a dramatic climax and a rather extraordinary murder.

It's all very ingenious. However, I have to say that although Fletcher came up with a clever plot, she tested my ability to suspend disbelief to breaking point. I found the Leeds' behaviour odd and unconvincing, and the reports of the various suspects didn't hold my interest as it should have done. I wasn't convinced about the psychology of the characters, and in a novel of psychological suspense, that's quite a drawback. Even so, Fletcher was a dab hand at keeping you guessing, and for that reason, this story is worth reading.

Wednesday, 17 April 2019

The CWA Annual Conference in the Lake District

I'd barely had time to get my breath back after my trip to Toronto when I was on the road again - not such a long journey this time, though. An hour and a half up the M6, the CWA annual conference was being held at Bowness-on-Windermere in the superb Macdonalds Old England Hotel, right on the bank of the lake. And it was a very special occasion for me, as it marked the end of my term in office as Chair of the CWA. More about my time in the hot seat another day.

In partnership with Cumbria Libraries, we'd arranged a series of library events for conference delegates, and I took part in three of them. The first was a solo effort at Kendal's Carnegie Library, swiftly followed by a trip to Ulverston Library, where I featured in a panel along with Jean Briggs (who was the lead organiser for the conference) and Shetland's Marsali Taylor. A pleasant late evening meal with Marsali was followed the next day by a trip to Ambleside Library, where I was a member of a panel including Kate Jackson and Christine Poulson. Then the conference began with a prosecco reception, and a short talk by Mike Craven and myself about Lake District mysteries before a dozen of us dined together at a local restaurant.

On Saturday, we had a terrific presentation by a husband and wife team comprising a forensic psychologist and a detective constable, followed by a talk from David Donachie, Chair of the Society of Authors. In the afternoon there was a choice of activities, and I opted for a two-hour sail on Windermere, up to the north end of the lake. Blustery but fun - and it didn't rain all weekend, rather incredibly!

Then came the CWA AGM, culminating in the moment when I officially handed over as Chair to Linda Stratmann, with Jean coming in as a new Vice Chair. It wasn't poignant so much as truly gratifying to see the membership, and the organisation as a whole, in such good heart. A gala dinner followed, with an after dinner speech by a former Police and Crime Commissioner. Sunday saw talks by a retired detective, a leading criminal barrister, and a literary agent, and then in the afternoon there was a "Cupcakes and Crime" event in which I formed part of a panel with Christine, Peter Lovesey, Mike, and Kate Ellis. Another convivial dinner, and then on Monday a trip to Grasmere and Hawkshead before the homeward journey.

The CWA conference is always a great event, and though I'm not impartial, I found this one especially memorable and enjoyable. As ever it was good to catch up with old friends, such as Keith Miles, Robert Richardson, and Sarah Ward, as well as to meet talented members of the new generation of writes such as Vicki Goldie, Eva Cserhati, and Alex Chaudhuri. And my very best wishes go to Linda as my successor.

Monday, 15 April 2019

The New Girlfriend - 2014 film review

Ruth Rendell was an exceptionally gifted writer of short stories as well as novels, and I read her story "The New Girlfriend" a long time ago and enjoyed it. Only recently did I discover that it was filmed five years ago by the talented French director Francois Ozon. Turning a short story into a film is often problematic, because of the need to stretch out a rather slender storyline. Ozon wrote the screenplay himself, and solved the problem by creating an erotic drama that borrows from the genre of crime and suspense but does not really belong to it.

Anais Demoustier plays Claire, who forms an intense friendship with another young girl, Laura (Isild Le Besco). The two girls meet handsome young men whom they marry, but they remain close. Laura gives birth to a daughter, but falls ill and dies. Claire vows to take care of Laura's husband David (Romain Duris) and the little girl, but is startled when she calls at their home and finds David dressed as a woman.

Once she has overcome her initial shock and distaste Claire becomes increasingly drawn to David, or at least to his alter ego Virginia. The plot thickens, and so do the sexual complications. As a reviewer on rogerebert.com says, Ozon "transforms what might have been a tonal nightmare in other hands into a wildly entertaining work, one that manages to be simultaneously funny, touching, slightly unnerving and undeniably sexy to behold, regardless of where your predilections may lie."

Some reviewers have termed the film "Hitchcockian", but although I can see why they say this, given the tricky way in which the story develops, it's a misleading description. I was expecting a crime film, and it took me a while to realise that Ozon (although he's worked in the crime genre, and is clearly fascinated by it) was here going in a different direction. But once I'd understood what he was trying to do, I was impressed.

Anais Demoustier plays Claire, who forms an intense friendship with another young girl, Laura (Isild Le Besco). The two girls meet handsome young men whom they marry, but they remain close. Laura gives birth to a daughter, but falls ill and dies. Claire vows to take care of Laura's husband David (Romain Duris) and the little girl, but is startled when she calls at their home and finds David dressed as a woman.

Once she has overcome her initial shock and distaste Claire becomes increasingly drawn to David, or at least to his alter ego Virginia. The plot thickens, and so do the sexual complications. As a reviewer on rogerebert.com says, Ozon "transforms what might have been a tonal nightmare in other hands into a wildly entertaining work, one that manages to be simultaneously funny, touching, slightly unnerving and undeniably sexy to behold, regardless of where your predilections may lie."

Some reviewers have termed the film "Hitchcockian", but although I can see why they say this, given the tricky way in which the story develops, it's a misleading description. I was expecting a crime film, and it took me a while to realise that Ozon (although he's worked in the crime genre, and is clearly fascinated by it) was here going in a different direction. But once I'd understood what he was trying to do, I was impressed.

Thursday, 11 April 2019

Sherlock and Toronto

In January last year, I had the pleasure of delivering the annual lecture to the Baker Street Irregulars at the Yale Club in New York City. Whilst I was there, I met Cliff Goldfarb, and some of his colleagues from the Toronto-based Friends of the Arthur Conan Doyle Collection. This is a collection of Doyleana at the magnificent Toronto Reference Library. And Cliff and co invited me to give the Cameron Hollyer lecture at the Library this year. Given my enthusiasm for Toronto, I wasn't going to turn down the chance of a return trip, and I've just got back home, having squeezed it in prior to the CWA annual conference.

One setback in the run-up to the lecture was that last week I caught a cold. And early on Friday morning, when I was due to fly out, I found I had more or less lost my voice. Not ideal just before a long flight and a lecture. But to cut a very long story short, I made it to Toronto in one piece, and had a restful and pleasant evening in the hotel.

Then, after a quiet morning, I found my voice was working more or less acceptably, and made my way to the Library. There was a good turn-out, and I was very glad (and very relieved) that I managed to get through the lecture, and that all went well. I was also given a tour of the Collection, which I must say is very impressive. Among other things, I was shown a first edition of A Study in Scarlet - wow! And several other fantastic items, including Doyle's early writing which anticipated Sherlock's debut.

The rest of the trip went extremely well and was full of pleasurable things, including a splendid meal with my hosts at the Toronto Lawn Tennis Club, a boat trip to the islands, and a chance to catch up with old friends including lunch with Peter Robinson, who divides his time between Canada and the UK. Then it was time to get back home, a bit weary, but very glad that I'd made the trip.

Wednesday, 10 April 2019

Gallows Court shortlisted for the eDunnit award - and reader reaction

I got back home yesterday after a long flight from Toronto (more of which anon) to receive the delightful news that Gallows Court has been shortlisted for the eDunnit award for best crime ebook of 2018. If ever there was a splendid cure for jetlag, that was it!

The eDunnit is awarded each year at CrimeFest, and as regular readers of this blog will know, I've attended CrimeFest ever year since its inception. This year, alas, I can't make it to Bristol - although for a very good reason which I'll mention another day. But I'll certainly be there in spirit!

The shortlist comprises seven books, and Gallows Court finds itself in excellent company. The other authors include a number of old friends, and the stellar list in full is: Leye Adenie, Steve Cavanagh, Laura Lippman, Khurrum Rahman, Andrew Taylor, and Sarah Ward. Congratulations to everyone, and also of course those shortlisted for the other CrimeFest awards.

This sort of thing is always a boost to morale, and the announcement was particularly well-timed as I continue to work on the sequel to Gallows Court. Back to the keyboard now with renewed vigour! It's a few years since a novel of mine was shortlisted for an award - the most recent was The Arsenic Labyrinth - and the reaction to Gallows Court continues to thrill me.

On that subject, I've had two especially fascinating and distinct reactions from readers to the new book. I heard the other day from Mary Harris, who is part of a readers' group in Elgin, Scotland, and she gave me a fascinating insight into their deliberations about the book. This sort of feedback is always rewarding. And some time ago, I received some incredibly interesting responses to the story from Cionaodh MacantSaoir as he was actually reading the novel, which charted his evolving reactions to the plot twists and so on. I haven't yet had time to figure out with him a way of sharing his thoughts on the book more widely, but I think it might be fun to do so. It was certainly wonderful to get insight into a thoughtful reader's evolving perceptions of a story with many twists.

Monday, 8 April 2019

Cathy Ace - Guest Post

Today I welcome to the blog Cathy Ace, a friend, fellow writer (most recently of the very enjoyable The Wrong Boy), occasional quiz team colleague, and former Chair of the Crime Writers' of Canada, who contributes some thoughts about place in crime fiction.:

"Wish

you were here…?

I should begin by telling you that I LOVE

my life and where I live it. Truly. I am a deeply contented person. So when I

say I read to “escape”, please don’t get the wrong idea – I’m not trying to

escape from anything; no, I want to

escape to the worlds authors create.

You see, one of the things I enjoy most about reading crime fiction is the

chance to travel more widely and to get to know places in more depth, and

differently, than I could possibly manage in one lifetime. And I’m a person who

has traveled, and continues to travel, a great deal – I even migrated from

Wales to Canada aged forty!

I might induce some blushing from my host

when I say this, but one of the aspects of Martin’s writing I most admire is

his ability to portray the soul of an area or location. And by reading those

who are good at conveying not just the physicality of a place but also how it feels, I hope my own ability to do the

same stands a chance of constantly improving, and sharpening. I truly believe

that where a story is set is critically important to the reader’s experience of

that story; a lack of a sense of place in a book leads – for me – to an

incomplete experience of the tale being told.

It might be that the cultural or natural

setting is critical to the plot, or that local history plays a role. Possibly

there’s an architectural location with a particular quirk of design, or an

especially dangerous/deadly “beauty spot”. The setting can provide the

opportunity for a twist, or an entire plot, and mould characters’ cores. It

also allows for the delicious tension between those who are bred to it in their

bones and those who are in-comers or visitors…so many possibilities for an

author whose aim is to draw readers into their work and allow them to

experience, rather than simply read, their story.

As storytellers – which is what I strive to

be my best to be – we want those reading our tales to become immersed in them. Delivering

a fulfilling sense of place is the novelist’s way of “setting the stage” upon which

their drama can play out once the curtain is raised. For me.

How do you feel about “place” in the books

you read?"

You can find out more about Cathy and her

work at her website: http://www.cathyace.com/

Friday, 5 April 2019

Forgotten Book - Dominoes

John Wainwright was a former police officer who became a prolific crime writer. As I've mentioned before, he was successful in his day, but his reputation has not survived his passing. There's a tendency, I think, to dismiss him as a mass-producer, which he certainly was - but there was more to him than that.

Wainwright was a much more ambitious novelist than some might think. A good example of the way he tried to stretch himself as a writer can be found in Dominoes, published in 1980, at the time when Wainwright was about at the peak of his powers. It was his fiftieth novel, and The Times called it "gripping, and worryingly memorable".

The story begins brilliantly, with a passage narrated in the first person by a man who describes the moment "when I decided that I must kill Gerald Morley". The reason is clear - Morley is being blamed for the suicide of the narrator's wife, a teacher. It looks as though we are in for a conventional form of "inverted mystery". But then the story shifts and we are presented with a wilful young woman who fleetingly crosses the narrator's path; she is wealthy but unkind, with a snobbish disdain for the poor and vulnerable.

I thought the build-up of tension was extremely well done. This part of the story was indeed gripping. The trouble is that the second half of the book is less satisfactory. Wainwright is venturing into the realms of psychological suspense, and links in a police investigation, described with his customary crisp authority. But for me, a key psychological revelation fell flat, because I didn't think it adequately foreshadowed - not the first time I've encountered this with Wainwright - and I felt somewhat frustrated. There is a really good book in here, trying to get out, but I think that it can't be counted a complete success. And this is where, I suspect, Wainwright sometimes went wrong - because he was so industrious and productive, perhaps he didn't devote quite enough time or thought to exploring the complex psychological behaviours he was seeking to portray. But I admire the way he took risks with his books, and wasn't content to stick to a formula. This novel is a good example of his considerable strengths as a novelist, as well as his limitations.

Wainwright was a much more ambitious novelist than some might think. A good example of the way he tried to stretch himself as a writer can be found in Dominoes, published in 1980, at the time when Wainwright was about at the peak of his powers. It was his fiftieth novel, and The Times called it "gripping, and worryingly memorable".

The story begins brilliantly, with a passage narrated in the first person by a man who describes the moment "when I decided that I must kill Gerald Morley". The reason is clear - Morley is being blamed for the suicide of the narrator's wife, a teacher. It looks as though we are in for a conventional form of "inverted mystery". But then the story shifts and we are presented with a wilful young woman who fleetingly crosses the narrator's path; she is wealthy but unkind, with a snobbish disdain for the poor and vulnerable.

I thought the build-up of tension was extremely well done. This part of the story was indeed gripping. The trouble is that the second half of the book is less satisfactory. Wainwright is venturing into the realms of psychological suspense, and links in a police investigation, described with his customary crisp authority. But for me, a key psychological revelation fell flat, because I didn't think it adequately foreshadowed - not the first time I've encountered this with Wainwright - and I felt somewhat frustrated. There is a really good book in here, trying to get out, but I think that it can't be counted a complete success. And this is where, I suspect, Wainwright sometimes went wrong - because he was so industrious and productive, perhaps he didn't devote quite enough time or thought to exploring the complex psychological behaviours he was seeking to portray. But I admire the way he took risks with his books, and wasn't content to stick to a formula. This novel is a good example of his considerable strengths as a novelist, as well as his limitations.

Wednesday, 3 April 2019

Gallows Court in paperback

Gallows Court appears in paperback tomorrow, and I'll be at Waterstones in Knutsford tomorrow afternoon to sign copies by way of celebration. It's always exciting when a new book comes out. It may seem surprising to some, but I feel at least as much pleasure now as I did when my earliest books hit the shelves. I've never regarded writing crime stories as a formula or a chore, even though it is often a challenge. Each book, for me, represents a different kind of experience. This is equally true with books in a series. I try to give each one a distinctive personality, while striving to retain the qualities that made the book appealing to a publisher and readers of the series in the first place.

Gallows Court has been a happy and a lucky book for me, and I've been delighted by reviews and general reaction to it. One can never please everybody, and indeed it's futile to try to do so, but I have been pleasantly surprised by the breadth and strength of the positive response to the novel. There were times when I was writing the book when I worried whether it would ever see the light of day. Remembering those moments of self-doubt is important - definitely something to keep in mind the next time that self-doubt strikes...

This year, I've been devoting more time to writing than ever before. Not just to the writing life - travelling to events and so on, though there is a lot of that to come, very soon - but to getting down to putting words on the page. And I've enjoyed it.

First and foremost, I've been concentrating on the sequel to Gallows Court, Mortmain Hall. I'll talk more about this novel when it's finished and my agent and editor have seen it, but I'm feeling very hopeful about it. In addition, since the new year, I've written a short story about the Peterloo massacre, an essay for a true book about the Harold Shipman case, a lecture about Sherlock Holmes and the Detection Club, and an essay for an academic reference book. Quite a mixed bag. And that sort of variety does help me to keep fresh, and makes it easier to keep my writing fresh.

More of those other projects in the future. Just for the moment, I'm allowing myself to celebrate Gallows Court!

Monday, 1 April 2019

Research, travel, and writing

This year, I'm involved with a good many library events of one kind or another, and there are also books to be written and to be researched. So when I was invited to give a talk about Gallows Court at Middlesbrough Central Library, I thought it would be a good plan to combine the trip with some research activity, mainly related to my work-in-progress, Mortmain Hall, which will be the sequel to Gallows Court.

A key setting in Mortmain Hall is on the Yorkshire coast, and although the Mortmain peninsula doesn't exist, the real-life places that were its inspiration are Flamborough Head and Ravenscar, two fascinating spots that I wanted to take a closer look at. Why do this, when the setting in the book is invented? My reasoning is that although my books are most definitely works of fiction, I like them to have that "feel" of authenticity that only comes from seeing for oneself how the land lies. I'm not trying to get background precisely right in a slavish or pedantic way, but rather to get a sense of atmosphere, as well as seeking a clue about specifics (an obscure example, for instance, being: what sound do stonechats make when they sing in the Yorkshire grassland?) which help to give the narrative touches of depth. And I was very lucky that last week's excellent weather made the trip delightful as well as informative.

Flamborough Head is a peninsula to the south of Scarborough, with a limestone and fascinating chalk cliffs. Ravenscar, just north of Scarborough, is a place which made a great impression on me when I was a boy; during a holiday, my parents took me there, to "the town that never was". Ravenscar was, at the end of the nineteenth century, intended to be transformed into a new seaside resort. But the company which ran the enterprise collapsed, and only a few buildings and roads were left. The result was eerie but also highly atmospheric. I loved having the chance to spend time there, and to explore the local area as well as staying at the excellent old Raven Hall Hotel - a great place, with its own battlements and some interesting wildlife nearby...

And then it was on to Middlesbrough, via two fishing villages, Robin Hood's Bay and Staithes, which might just have inspired another story setting. Yes, I came away with rather more research material than I can fit into Mortmain Hall, which was a real bonus. It's nearly nine years since I last gave a talk at the excellent Central Library, as I discovered to my surprise when I checked this very blog to see what I said about that trip in 2010, and I was delighted to make a return visit. And to sign copies of the new paperback, and to meet Richard, of Drakes' Bookshop in Stockton. All in all, a trip that was both enjoyable and invaluable.