Among the great pleasures of this past year was having the chance to catch up with a number of people I'd not seen for quite some time. A particular highlight was a lunch with the dedicatees of Hemlock Bay, Ann, Lea, and Jo, who have been my PAs for a combined total of more than 30 years. There were also some truly poignant moments. This was the year when we lost - among others - David Stuart Davies and Catherine Aird, two stalwart members of the Detection Club, and both good friends for many years, as was Peter Lewis, who published a novel and an anthology of mine and was one of the first crime writers I ever met. We also lost John Pugmire, a locked-room-mystery-loving Brit who lived in the States and with whom I had a memorable train trip from New York to Washington DC the morning after I won an Edgar. David's widow asked me to speak at his funeral, something I've never done before, and that was for me a very emotional occasion. Some other dear friends suffered severe ill-health and I hope fervently for happier news from them next year.

Tuesday, 31 December 2024

2024 - People

Among the great pleasures of this past year was having the chance to catch up with a number of people I'd not seen for quite some time. A particular highlight was a lunch with the dedicatees of Hemlock Bay, Ann, Lea, and Jo, who have been my PAs for a combined total of more than 30 years. There were also some truly poignant moments. This was the year when we lost - among others - David Stuart Davies and Catherine Aird, two stalwart members of the Detection Club, and both good friends for many years, as was Peter Lewis, who published a novel and an anthology of mine and was one of the first crime writers I ever met. We also lost John Pugmire, a locked-room-mystery-loving Brit who lived in the States and with whom I had a memorable train trip from New York to Washington DC the morning after I won an Edgar. David's widow asked me to speak at his funeral, something I've never done before, and that was for me a very emotional occasion. Some other dear friends suffered severe ill-health and I hope fervently for happier news from them next year.

Monday, 30 December 2024

A Haunting in Venice - 2023 film review

When Agatha Christie's Halloween Party finally appeared in an affordable paperback edition for the first time, I snapped it up right away. I was still a teenager, and I'd read all her mystery novels and was impatient for another one. But although it definitely had some pleasing ingredients, I remember that my over-riding emotion was one of dismay. I'd hoped (naively, given that I'd already been disappointed by Third Girl) for something reminiscent of the better Poirot stories, but this novel felt like a real let-down.

With that in mind, I decided to take a look at the newish film based on the book, A Haunting in Venice, the third Poirot film directed by and starring Kenneth Branagh. I watched his version of Murder on the Orient Express not long after it was released, but I found Michael Green's screenplay soporific and the whole exercise pointless. With that in mind, I didn't bother with Branagh's take on Death on the Nile. But that book, again, was a Poirot masterpiece. It stuck me that, given the problems with Halloween Party, Green (who is again responsible for the screenplay) might actually have improved it. Unfortunately, I don't think he did. His version of the story is utterly different, but - at least in my opinion - unsatisfactory in a whole new variety of ways.

Let me start with the strength of the film. Visually, it's terrific. Venice is, of course, utterly photogenic, and has formed the backdrop to so many great films, including one of my all-time favourites Don't Look Now, as well as some that aren't so good. The decision to set the story in a crumbling palazzo that has nothing to do with the original Christie novel was bold and imaginative and, I think, justifiable. But one comes back to the central question - what is the point of this film?

Sir Kenneth Branagh is a talented and successful actor and director and I'm simply baffled as to why he wants to play Poirot. He can't hope to match the brilliance of David Suchet's portrayal of the character; that's fair enough. But his tortured version of the great detective seems to me to be inferior to the portrayals by both Albert Finney and Peter Ustinov. As for Tina Fey's American version of Ariadne Oliver...

I'm definitely not one of those who doesn't believe that Christie's stories can't (or shouldn't) be adapted in fresh and ambitious ways. It makes perfect sense for the Christie estate to explore new ideas. But I think they work best if the writer tries to stay true, however indirectly, to the author's original vision of the story. Having said that, there's no denying that this film has been a commercial success. So perhaps making money is the point, simple as that. All I can say, regretfully, is that this version of the story was not for me.

2024: Places

I've enjoyed exploring a lot of places this year, in Britain and further afield, and as usual these trips have regularly proved inspirational. One or two places have already given me fresh settings for stories that I'm working on. For the first time in ages, I went to Ireland - twice, for good measure - on tours that enabled me to see a good deal of the lovely countryside. One trip included northern Ireland and at last I managed to see the Giant's Causeway, somewhere that's been on my bucket list for a long time. In the republic, places like Donegal, Malin, and the cliffs of Moher are among those that linger in the memory. There were also lovely visits to Scotland (including Culzean Castle and the charming artists' town of Kirkcudbright as well as the book town Wigtown) and Wales.

Three trips involved more extensive travelling. One of the many highlights of a yacht cruise around Croatia, which ended up in Venice, was the chance to drink a Bellini in Harry's Bar - a memorable occasion for all sorts of reasons! Croatia is a gorgeous country, and this was my second trip in as many years. Some of the small coastal villages and towns are crammed with history. The same is true of northern Spain. A visit to the Guggenheim in Bilbao was fascinating, and the resort of Gijon was a revelation, a place I'd never heard of, but which really appealed to me.

Bouchercon this year was held in Nashville, in a vast and - in some respects - bizarre hotel in which many of us kept getting lost. But I did have a fantastic suite with a balcony and lots of nice meals and drinks with friends. I was interested to visit the city, including the legendary Printers' Alley, where I had a meal in a 'British pub' with a number of friends. One of the highlights was a great place which offered whisky tasting. And there was a Madame Tussaud's devoted almost entirely to country and western music stars...

One of the many highlights of a yacht cruise around the islands and northern coast of Croatia, which ended up in Venice, was the chance to drink a Bellini in Harry's Bar - a memorable occasion for all sorts of reasons! Croatia is a gorgeous country, and this was my second trip in as many years. Some of the small coastal villages and towns are crammed with history. The same is true of northern Spain. A visit to the Guggenheim in Bilbao was fascinating, and the resort of Gijon was a revelation, a place I'd never heard of, but which really appealed to me.

Alibis in the Archive at Gladstone's Library and Bodies from the Library at the British Library are always very enjoyable. So was a trip to Cambridge to see a preview of the Murder by the Book exhibition. A real highlight (see the photo near the top of this post) was seeing All the Lonely People featured as one of the notable 100 British crime novels of the 20th century. A great moment! During the same trip, it was nice to spend a day in Rutland with David Whittle, biographer of Edmund Crispin and see places like Oakham and Rutland Water for the first time. It was fun to attend an E.C.R. Lorac exhibition at a library in Lunesdale and even more exciting to witness Lena Whiteley - above - unveil a plaque honouring Lorac at her old home, Newbanks, in Aughton.

Libraries - public libraries, not just Gladstone's and the BL - are very important to me. I organised exhibitions for libraries in the Wirral, Cumbria, and Warrington areas as well as at Bromley House in Nottingham. There were events at libraries in Penketh and Wallasey in June, while a trip to Cumbria involved four events at libraries in the area as well as the chance to revisit places like St Bees and Kendal. I even started thinking about ideas for another mystery novel set in the Lake District...I'm also very interested in getting young people enthused about crime fiction and as well as an online event with St Bede's, a sixth form college in the north east, I had the interesting experience of visiting Royal Lancaster Grammar School and meeting a bunch of students who had some really fascinating questions to ask about crime writing.

The year began with a family weekend celebration of my brother in law's 70th in Liverpool, and I spent time in Scotland and Wales, enjoying the scenery as well as conversations with local people. There were trips to Oxford, including meetings with more of my old college friends, and a poignant evening in Brooks' Club, London, when we celebrated the memory of my late tutor Don Harris, as well as a great night at Lincoln's Inn, listening to Matthew Syed, one of the journalists I admire most, in the company of my son and also some guys I last met as fellow students over forty years ago.

And as I've whizzed around, I've felt not only energised by the experience, but also thankful for the pleasure of the company of some lovely people. And a few of them will be featured in my final post of the year tomorrow.

Sunday, 29 December 2024

2024: Publications

2024 has been a busy and hugely positive year for me in so many ways. I'm really grateful for the good fortune I've had and one aspect of that has been the kind messages that I've had from so many readers of this blog. Believe me, they are very much appreciated. I'm now going to inflict on you a three-part review of the year from my perspective, starting with publications. There have been plenty of them, although as you can imagine, most of the writing I've done this year (for example, Miss Winter in the Library with a Knife) will not be published until next year.

My new novel for this year was Hemlock Bay. This is a book I'm really proud of, the fifth Rachel Savernake mystery. It was a lot of fun to write and I was delighted that it received a great reaction (something that one can never, ever take for granted, however optimistic one is about what one has written). There were great reviews in the Daily Mail and the Morning Star (political balance, you see...) and the book was runner-up in the list of crime books of the year in The Critic. Many bloggers, whose support is invaluable, were also very enthusiastic.

The fourth book in the series, Sepulchre Street, was published in paperback, and was shortlisted for the eDunnit crime book of the year award: enormously gratifying! The American edition was published while I was in Nashville, under the title The House on Graveyard Lane.

May saw publication in the UK of the revised and expanded paperback edition of The Life of Crime. This was one of the Guardian's books of the month, and there were some terrific reviews, not least in the Times Literary Supplement, which gave it extended coverage.

My only new short story to be published, 'The Widow', appeared in Midsummer Mysteries, the gorgeously produced anthology I edited for the Crime Writers' Association. Two previously published stories, 'No Peace for the Wicked' and 'End Game' enjoyed a new life in American anthologies. For the British Library, I edited two anthologies, Lessons in Crime and Metropolitan Mysteries. I also wrote introductions for ten novels reprinted in the British Library Crime Classics series, as well as an intro for a book of stories by Tom Mead, of which more soon. I published a variety of articles in different print and online publications, including articles in the Spectator, the Daily Telegraph, and the Catholic Herald. Not to mention more than 150 blog posts!

So there was always plenty going on. Right now, I'm writing as busily as ever. And, I like to think, to the highest standard I've managed over the years. But for a writer to thrive, he or she needs interested readers. I've been delighted by so many contacts with readers across the world. Their reactions are highly motivational and play a huge part in keeping me enthused about writing - as I certainly am, as much as I've ever been.

Thursday, 26 December 2024

The Three Deaths of Justice Godfrey by L.C. Tyler

In recent years I've become more interested than ever in the way that crime novelists draw inspiration (literary rather than homicidal) from real life criminal cases. The form that inspiration takes will vary from author to author. Sometimes it's indirect, perhaps to the point of being debatable if unacknowledged by the author. Sometimes it's fairly clear. And sometimes the story offers a retelling of the original story in fictional form, perhaps supplying a new, or relatively new, interpretation of the existing facts.

The case of Sir Edmund Godfrey, who died in 1678, has attracted a great deal of attention from crime writers as well as criminologists. Godfrey's body was found in a ditch near Primrose Hill after he had been missing for several days, and his death has been the subject of a wide variety of theories. Over the years, I've read three books about the case. The first is the most famous, and was written by John Dickson Carr. The second, three years ago, was The Bloodless Boy by Robert J. Lloyd, which was dark, atmospheric, and menacing. And now we have a lighter novel which turns the case into a nifty detective story, The Three Deaths of Justice Godfrey by L.C. Tyler.

I've spoken several times on this blog about my enthusiasm for Len's humorous series about Ethelred Tressider and Elsie Thirkettle, but this book is the tenth entry in a very different series, featuring the magistrate Sir John Grey. Here Grey sets about investigating the mystery surrounding Godfrey's fate. The John Grey books are historical stories, but although they are relatively serious, Len blends his well-researched plot material with touches of wit. I like in particular Grey's wife Aminta, who is given some of the best lines.

A historical note, running to more than eleven pages, appears at the back of the book, and it provides an excellent summary of the competing ideas about the case. If spoilers were removed, it would make a very good stand-alone essay. Len also explains where, and why, he deviated from complete fidelity to the historical record. I suspect we'll never be sure about the truth of the case, but Len's arguments are, as I would expect, well-marshalled and cogent.

Tuesday, 24 December 2024

Merry Christmas!

I'd like to wish all readers of this blog a very merry Christmas. And what better moment to mention my new novel for 2025? As the picture indicates, this is a Christmas mystery novel called Miss Winter in the Library with a Knife and it will be published by Head of Zeus/Aries in September next year.

In the past I've written Christmas short stories - a Harry Devlin tale, long ago, called 'I Say a Little Prayer', and more recently 'End Game' - but this is my first Christmas novel. And it's a novel with puzzles, as well as a Cluefinder, so there is an interactive element.

I've been extremely pleased by the initial response to the book, from bloggers and commentators, and also from overseas publishers who have been seeking translation rights. So this may be an augury of more good things to come.

But that's for the future. Right now, it's time to enjoy 'the most wonderful time of the year'. I hope you have a really good Christmas and look forward to writing more for you in 2025.

Sunday, 22 December 2024

Catherine Aird R.I.P.

I was deeply saddened to learn of the death yesterday, following a severe stroke, of Kinn McIntosh M.B.E., better known to crime readers as the Diamond Dagger winning author Catherine Aird. She was 94, born in the same year that the Detection Club, of which she was a loyal member for more than forty years, was founded. Catherine - I'll use that name in this post - is someone who has been a friend for more than thirty years. I always enjoyed her writing - in fact I read and reviewed Parting Breath on this blog just three weeks ago - but more than that, I had huge admiration and respect for her as a person.

As an author she will be remembered for twenty-six novels, almost all of them featuring her Calleshire cop DI Sloan, as well as a good many short stories. One of those stories, by the way, is due to appear in a forthcoming Detection Club anthology next March. Whenever I approached her with a view to writing a short story, she was always glad - and quick - to oblige. She really enjoyed the short form. Her fiction pays tribute to Golden Age traditions whilst remaining distinctive - and consistently witty.

I first met Catherine through the CWA, which she chaired for a year in 1990-1. She was a charming and supportive companion to her many friends and a leading figure in the Dorothy L. Sayers Society as well as in the Girl Guide movement. She suffered ill-health in her youth, and I think that health problems probably troubled her for the greater portion of her life. But she was uncomplaining and great fun. I have a prized photograph, taken by the Independent newspaper, of several of us, including Val McDermid, Chaz Brenchley, and Catherine, wandering around under Brighton pier during a CWA conference. Another treasured memory is of spending a good deal of time with her during the 2015 CrimeFest at Bristol, when she was a guest of honour. We were on a 'forgotten authors' panel together, and she joined my wife and me and other friends for a very enjoyable evening. So was the Daggers Dinner at which she was awarded the Diamond Dagger.

I last saw her in person when I visited her at her home in Sturry, near Canterbury, two and a half years ago. By that time her mobility was much diminished, but her good humour and lively intelligence were much in evidence. She very kindly gave me a number of books from her collection, as well as signing several of her books that I'd collected over the years, and writing a few notes about the background to each. During the course of the day neighbours kept popping in to see that she was okay. She was, at that time, working hard on her next novel. It was an extremely pleasant day and quite a real privilege to see her in the home she'd had since the late 1940s. From time to time she'd drop me a line, to pass on information about crime fiction heritage that she thought would be of interest to me. And it always was. I shall miss her a great deal.

Friday, 20 December 2024

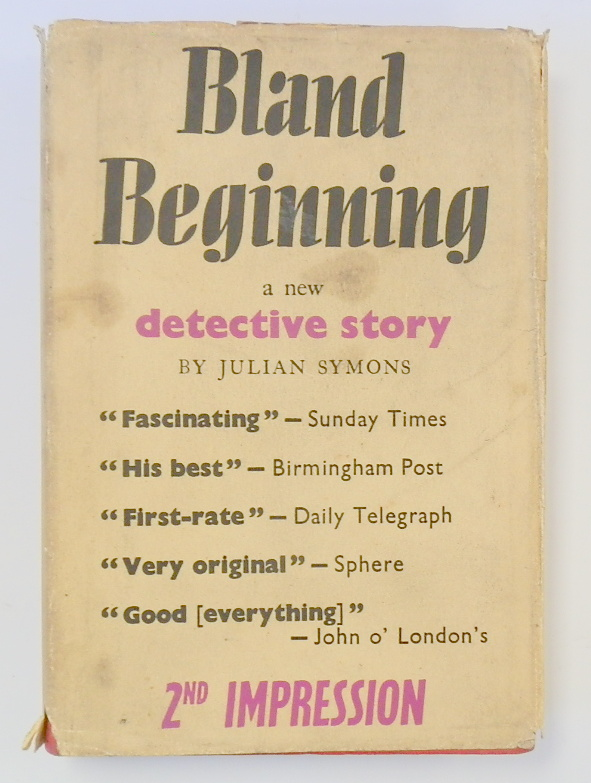

Forgotten Book - Bland Beginning

I must at some time have read Julian Symons' early (1949) mystery Bland Beginning, but it left no impression on me. Having now had another read of the story, I guess that partly this is due to the fact that I probably read it the best part of forty years ago, partly due to the fact that the story is about old (and possibly forged) books, so it's a bibliomystery - and while such stories didn't appeal too much in my younger days, they do now. I really enjoyed this one.

The title references the fact that this story, set in 1924, is a sort of prequel to Symons' earlier detective novels, in that it introduces (at a late stage) a young man who indulges in amateur detection and is in fact, Bland, the inspector who was Symons' first series character. It was also Bland's final appearance, as Symons turned decisively against the use of series detectives and also segued from traditional detection to psychological suspense.

Symons was more interested in, and more adept at writing, carefully plotted detective stories with a twist than he liked to admit in later life, and than his various detractors have acknowledged. This is, in some ways, an apprentice effort, but it's written with exuberance and good humour and the storyline derives from the Thomas Wise forgery case. There is even a gesture towards the Cluefinder! At the end of the story, a footnote refers back to an early clue.

The mystery concerns an attempt by four nicely contrasted young people to uncover the secret of some apparent forgeries of a book of poems by a long dead author called Martin Rawlings. Some of the poems are included in the text, and it's worth paying attention to them. Symons was a poet himself - in the Thirties he edited a poetry magazine - and this book includes a dedicatory poem to his baby daughter Sarah, whose sad death as a young woman would later cast a cloud over Symons' life. Symons' lifelong love of cricket is well to the fore in this story (it crops up in some of his later and better-known novels too) and there's a dramatic finale on the cricket pitch. Very good light entertainment.

Wednesday, 18 December 2024

Short Stories

Two of my short stories have recently appeared in lovely American anthologies. The first is 'No Peace for the Wicked', which is included in an Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine collection edited by Janet Hutchings and titled Twisted Voices. Janet has just announced her retirement after a long and distinguished career as editor of EQMM. I first met her in New York City back in the mid-90s and I've spent a good many happy hours in her company since then.

Janet has accepted many of my short stories for inclusion in EQMM and 'No Peace for the Wicked' is the most recent. There was a mishap with its original publication, when the final part of the story was omitted, rather in the manner of 'Lady Don't Fall Backwards' in that famous Tony Hancock show. But all was well in the end, and I'm delighted to see it in this book. Janet discussed the concept with me when we had a drink together at Malice Domestic last spring and said she wasn't sure what the title should be. Given that the connecting theme was unreliable (or unusual) narrators, I suggested Twisted Voices and she very kindly acknowledges this in the book. There are stories by some wonderful writers, including Ian Rankin and Joyce Carol Oates, and I'm very glad to be part of the project.

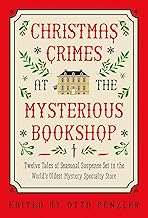

The second collection is seasonal - Christmas Crimes at the Mysterious Bookshop, edited by Otto Penzler. This includes my story 'End Game', which Otto commissioned from me last year. Each year the bookshop gives a copy of the latest Christmas mystery to its most valued customers, and some wonderful writers have been commissioned by Otto over the years. Again, I'm truly thrilled to be rubbing shoulders, at least as far as our stories go, with such luminaries as Jeffery Deaver Thomas Perry, Ragnar Jonasson, and Laura Lippman.

I haven't written many short stories this year, though 'The Widow' appeared in Midsummer Mysteries, the 2024 CWA anthology. This is simply due to lack of time, because of my other writing commitments. However, two more of my stories are slated to appear next year, and in 2025 I'll be editing no fewer than five anthologies. More details before long. In the meantime, I'm delighted to see these two collections.

Monday, 16 December 2024

The Desperate People - vintage TV review

The Desperate People, first screened by the BBC in 1963, is said to be the earliest of the Francis Durbridge TV serials to survive in its complete form. There's always, of course, the hope that long-lost episodes will eventually come to light, but in the meantime I'm very glad to have the chance to watch this show, which I'd never come across before.

As usual, there are some very capable actors in the cast. Denis Quilley plays the successful photographer Larry Martin, while Nigel Hawthorne is entertainingly cast as an out-and-out villain whose methods are much less subtle than those he demonstrated years later as Sir Humphrey Appleby in that wonderful comedy Yes, Minister. Renny Lister (wife of Kenneth Cope, who died recently) is Larry's secretary and potential love interest, while Stanley Meadows and June Ellis, who also had major roles in subsequent Francis Durbridge serials, also contribute to the cliffhanger-heavy excitement.

The first episode in particular is full of plot twists. Larry is visited by his brother Phil, who is about to set off for Dublin. Phil tells Larry about the death of a colleague and his plan to visit the widow, and shows Larr a photo of the couple. But instead, Phil heads for a hotel, where (despite his lack of interest in poetry) he takes a remarkable interest in a book of poems by Hilaire Belloc. Phil is found dead in his hotel room and the inquest verdict is suicide, but Larry isn't satisfied and visits the hotel, encountering several people who act suspiciously. A colleague of Phil's is then shot from a passing car. In a delirious state he makes an enigmatic remark about a photograph. And then Larry receives a photograph of his brother, which should be in a display case outside his studio. Instead, it's been replaced by the photo of the mysterious couple that Phil showed him.

And all that is in the first twenty-five minutes! Francis Durbridge was an absolute master of the art of mystification, and he does manage to explain everything by the end of episode six. Yes, you have to suspend your disbelief, but this is very agreeable escapist viewing. And with none of the padding that disfigures so many big-budget TV serials of the present day.

Friday, 13 December 2024

Forgotten Book - The Disappearance aka Echoes of Celandine

When I met Nicholas Royle at the Richmond festival a few weeks ago, it turned out that we had a shared interest in the work of Derek Marlowe, of whom Nick is a great admirer. A couple of days later, Nick kindly sent me a copy of a Marlowe novel I hadn't read; it's the film tie-in Penguin edition of The Disappearance, which was originally published in 1970 under Marlowe's own, more evocative title Echoes of Celandine.

On the surface, this is a story about one of the most hackneyed thriller plots imaginable: a criminal is lured into undertaking 'one last job' prior to retirement, and mayhem ensues. The criminal in question is a hired killer, an ex-soldier who is ruthlessly efficient in hunting and destroying his prey. But in Marlowe's hands, the familiar material becomes strangely unsettling. Yes, there is pace and there are numerous plot twists. Yes, there is violence and quite a lot of misogyny (there are some scenes that wouldn't be written, or published, today, in my opinion). But this is also a literary novel of considerable merit.

I admire crime novels that are written with ambition by authors who are trying to do something different. And I'm definitely prepared to forgive such writers if what they produce doesn't quite work as well as it might have done. Give me a Sayers novel, however flawed, any day over (say) half a dozen Patricia Wentworth stories about Miss Silver. And Marlowe's ambition is clear. He's writing a study of character and mental disintegration, coupled with a strange, twisted love story. Yes, the book has various failings. But it's never less than intriguing.

Marlowe's writing was distinctive and stylish, if at times somewhat mannered, in A Dandy in Aspic. The same is true of this novel. Jay Mallory, our narrator, has grown weary of killing people (although he is responsible for several deaths in this book) and is obsessed with the need to find his gorgeous but unreliable wife Celandine. That quest drives his actions from start to finish. Along the way, there are some terrific lines, often laced with cynical humour. And a very dark ending.

I haven't seen the film based on the book, which starred Donald Sutherland, but even though I assume it wasn't a great success, I'm interested to see what the film-makers made of such an intriguing scenario.

The Day of the Jackal - Sky Atlantic - episode 10 and TV series review

I've enjoyed watching The Day of the Jackal, with tonight's final episode living up to the standards set by the previous nine in this Sky Atlantic TV series. Yep, ten episodes - a lot more screen time than the excellent film from 1973 - so naturally there's quite a bit of padding. But thanks to a truly mesmeric performance by the brilliant Eddie Redmayne as the cold-blooded killer nicknamed the Jackal, and several scenes of gripping suspense, the series was a success.

How much does the TV show owe to Frederick Forsyth's original novel, a masterly thriller which I devoured with relish as a teenager, as soon as it came out in paperback? Very little, is the answer. Yes, it tells the story of a brilliant assassin who prepares meticulously, and it involves a game of cat and mouse between those hunting him and the man himself. But overall, it's very different. (That's what they mean when they say the story has been 'reimagined'). But presumably it suited both Mr Forsyth and the TV company to make profitable use of such a well-known story brand.

Ronan Bennett's script, which brings the action into the present day, has great strengths and also some noticeable weaknesses. The idea of making the intended target of the Jackal's hit an IT mogul with a social conscience strikes me as inspired. I also like the way the shadowy figures who are responsible for hiring the Jackal are presented; their leader is Charles Dance at his most sinister, and he makes the most of his relatively limited screen time. Two other ingredients in the story helped to stretch the material to fit ten episodes, but didn't - in my opinion - work as well.

First, the Jackal may be a sociopath, but he is given a human side, with a wife (Nuria, played by Ursula Cobero) and child to whom he is devoted. He's even bought the family a fancy house in Spain and made himself vulnerable by doing his best to chum up with Nuria's useless brother and her mother. Given the Jackal's extreme ruthlessness (brilliantly shown in a flashback to Helmand, when he was still in the army), I didn't find the psychology of this scenario convincing, but such is Redmayne's skill as an actor that he just about persuaded me to swallow it.

Less effective, I felt, was the depiction of the MI6 hunt for the Jackal. Bianca Pullman (Lashana Lynch) is a mix of comic book action hero and soap opera character with a troubled family life and a working life plagued by useless and venal bosses. There were moments when these parts of the script resembled something AI might have cobbled together, so predictable and formulaic did they seem. Thankfully, there were a number of scenes - above all those in Helmand and the Jackal's murderous activities, perhaps most notably his scheme to shoot his target whilst the man went out for a swim - which were so powerful that the weaknesses paled into insignificance. And as a final episode bonus, it was wonderful to see Philip Jackson, better known as Chief Inspector Japp from Hercule Poirot, in a genuinely poignant and compelling cameo.

Wednesday, 11 December 2024

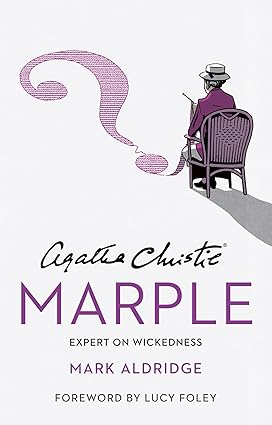

Agatha Christie's Marple: Expert in Wickedness

Mark Aldridge is one of a group of people, with John Curran to the fore, who are academic experts with a specialism in Agatha Christie. He's also one of a growing band of academic writers who is able to write accessibly in a way that will inform and also entertain a wide readership. His recent book about Hercule Poirot was a case in point, and now he's followed it up with Agatha Christie's Marple: Expert in Wickedness.

I've been a fan of Miss Marple ever since I discovered her at the age of eight thanks to the film Murder Most Foul (which I enjoyed) and The Murder at the Vicarage (the first adult novel I ever read, and one that I absolutely loved). So I fell on this book with enthusiasm, and I was not disappointed. It's a wide-ranging study, although not quite wide-ranging enough to include mention of the premiere of Murder Most Foul in a marquee in Great Budworth!

I'm the first to admit that - overall - the quality of the Poirot novels in terms of plotting is generally higher, but there are several very strong Marple novels. As well as The Murder at the Vicarage, I'm a big fan of The Body in the Library and A Murder is Announced, while I have a soft spot for 4.50 from Paddington, A Caribbean Mystery, and The Mirror Crack'd from Side to Side.

The approach of the book is basically chronological, and quite rightly the emphasis is on the novels and short stories featuring Jane Marple. However, there is also more than adequate discussion of the character's appearances on stage (in two plays based on the books), radio, film, and television. Personally I go along with the majority view that Joan Hickson was by far the best screen Miss Marple, but Mark Aldridge is quite generous to her successors, while pointing out gently that some screenplays based on books in which the character did not appear were not well-suited to having the old lady parachuted in. He includes some anecdotes related to the character and her creator with which I wasn't familiar. Overall, then, an enjoyable and worthwhile read.

Tuesday, 10 December 2024

The Best UK Crime Fiction Blogs and Websites in 2024

Yesterday I received an unexpected message from some people called Feedspot. They have created a Top Thirty of UK crime fiction blogs and websites. The details are here and if you take a look, you'll see that this blog ranks fourth. In fact, of the blogs created by a single person, it is top of the chart. So I'm duly gratified.

The list is said to rank the best blogs 'from thousands of book blogs on the web and ranked by traffic, social media followers and freshness'. When I enquired further, I learned that Feedspot's editorial team searches for relevant blogs and measures them against various criteria. I must confess that I don't really understand how such things are evaluated, since I've always been remiss in figuring out the technical side of things when it comes to my website and blog. I'm well aware that there are various techniques to improve search engine ratings, but I simply don't have the time or expertise to attend to these things as efficiently as would be ideal. Given the need to prioritise, my energies are focused on the actual writing of material rather than tech stuff. I'm pleasantly surprised that, on objectively assessed measures, the blog is doing so well.

Having said that, I should repeat what I've said before. I write these blog posts for one simple reason - because I enjoy doing so. There are all sorts of benefits to running a blog like this, most of which I never anticipated when I started out in 2007. The reason the blog is called Do You Write Under Your Own Name? is because, back then, despite the fact that I'd been a published novelist for sixteen years plus, relatively few readers were familiar with my work.

To some extent, this blog forms a record of my writing life, so that I can look back and remember past events and trips. That in itself is very rewarding. And it's a great memory jogger. There have been many times when I've been about to watch a film, for instance, only to check the blog and realise that I'd not only watched it before but written a review. Eeek! It's sometimes fun to watch again anyway and see if my opinion of the film (or, on occasion, TV show or novel) is the same as it was the first time around.

Above all, I value the personal contacts I've made through this blog. Some people who have got in touch over the years have become good friends. There are many who have given me information that is helpful to my researches - or just plain interesting. Your comments are always a delight to read. And the messages of encouragement I get from blog readers are enormously motivating.

At the moment, I feel my writing is going as well as it's ever done, perhaps better than it's ever done. There are several reasons for this, but undoubtedly they include the motivation I get from responses to my blog posts. I don't take these things for granted, believe me. I'm very grateful to all those people, from around the world, who support this blog. You've given me a great deal and I hope to return the compliment by keeping the blog going for a long time to come.

Monday, 9 December 2024

From Hemlock Bay to Whitley Bay

It's been a busy and enjoyable few days - unseasonally connected with the seaside! I was very pleased to see that The Critic magazine ranked Hemlock Bay as a runner-up in the list of crime books of the year. Thanks also to Mat Coward of the Morning Star: 'If you’re longing for a wholly satisfying Golden Age-style whodunnit, fully and fairly clued, and with every revelation followed by another twist, you need the 1930s-set Rachel Savernake series by Martin Edwards.'

So the book has had glowing reviews from both the Daily Mail and the Morning Star - definitely appealing across the political spectrum, I'd say! As if to celebrate, Apple is currently giving a special offer on ebook editions of Hemlock Bay - see the screenshot at the top of this post. A good way to bring the publishing year to a close.

Meanwhile, I've taken part in my last literary event of the year. This was a conversation with Ann Cleeves as part of Newcastle Noir. It was great to get back to the north east and to enjoy some sunshine in between the stormier moments. I visited Ann in her home town of Whitley Bay and she introduced me to a couple of local bookshops, both excellent, and one with a terrific second hand stock.

Life in Whitley Bay is, it must be said, rather calmer than life in Hemlock Bay, and none the less appealing for that. I had a very good time and enjoyed having a pre-dinner drink with Ann at the Spanish City before a very good meal at Hinnie's, a restaurant I last visited when Murder Squad was celebrating its 21st birthday. And next year, we will be 25...

Friday, 6 December 2024

Forgotten Book - He Arrived at Dusk

It's ten years since a review by John Norris of a book by R.C. Ashby (who was to become much better-known as Ruby Ferguson, a popular author of 'pony' books) aroused my interest in Ashby's crime fiction. It took a long time, but I've finally acquired a copy of He Arrived at Dusk, which John also reviewed, in laudatory terms, describing it as 'a little masterpiece', and comparing Ashby's skill at misdirection with Agatha Christie's.

Ashby wrote a number of detective novels and it seems that her forte was combining a fair play puzzle with strong elements of the supernatural. This is certainly the essence of He Arrived at Dusk, which was published in 1933. My copy is the Hodder file copy, which is dated 9 February in that year. It has crossed my mind that the timing was unfortunate, because this was just before Dorothy L. Sayers started reviewing crime for the Sunday Times. Had she covered this novel - and had she liked it - it would have given Ashby's career and reputation a significant boost.

My guess is that Sayers would indeed have liked it. This is not only a clever story, it is unusual and it is well-written (I am pretty sure Sayers would have approved the prose, which struck me as clear, but evocative and definitely better than the writing of many detective novels of the early Thirties). After an intriguing opening in a London club, we're plunged into a narrative written by a researcher called Mertoun, who is summoned to catalogue the library of Colonel Barr, who lives in a lonely house close to the coast of Northumberland. But Mertoun doesn't actually get to meet Barr, who is so ill that he remains in his room, fiercely guarded by Nurse Goff, who won't allow anyone - not even his nephew Charlie - to see him.

We soon hear about a strange local legend involving a Roman gladiator, a sort of ghost who haunts the locality. There have already been deaths in the Barr family and eventually someone else dies - but it is not Colonel Barr...

I did feel that the book lost some pace in the middle section, and when the narrator switches to the nurse's brother. But the finale is excellent and I appreciated the cunning with which Ashby had told a relatively simple story, embellishing it very nicely so as to create her surprise solution. Recommended.

Wednesday, 4 December 2024

Female Detectives in Early Crime Fiction:1841-1920

Jamie Sturgeon, a book dealer who has over the years supplied me not only with plenty of books but also with a good deal of interesting information about authors and their work, has kindly introduced me to a new book by Ashley Bowden, Female Detectives in Early Crime Fiction: 1841-1920: A Survey.

I thought I knew quite a bit about this subject until I read this book. I expected to see names like Dora Myrl, Judith Lee, Florence Cusack, Dorcas Dene, and Hagar Stanley, and I was not disappointed. But this valuable reference work contains a lot of information with which I wasn't familiar. Ashley Bowden has been reading and researching in this field for decades, and the result is a book which adds to our stock of knowledge in a concise and reader-friendly way.

Let me give just one example. I'd never thought of R.D. Blackmore, author of Lorna Doone, as a crime writer. However, eight years after publishing the one book by which he is remembered today, he was responsible for Erema, or My Father's Sin. The female detective in question is Erema Castlewood. Ashley Bowden gives us a short synopsis of the plot, but his verdict is not encouraging. Nor is the review he quotes from the Spectator: 'we think it to be unworthy of Mr Blackmore's talents.' Oh dear. I won't be rushing to read that one. But it's very useful to have the benefit of Ashley Bowden's view of the story as well as the review.

There are many good illustrations, and also a wealth of appendices, as well as (importantly) indexes. I suspect that I'll be consulting this book regularly in the future. There are a number of stories discussed here that I'd like to read, and several that sound as though they deserve to be back in print. So my thanks, once again, to Jamie as well as to Ashley Bowden.

Monday, 2 December 2024

Playing the Game

Puzzles are much in vogue at present, and this fashion is reflected in contemporary crime writing. In many ways, it seems to me that the public enthusiasm for puzzles such as Wordle and Murdle is comparable to the 'play fever' which swept the western world after the First World War and the influenza pandemic. This is the zeitgeist, I think. People want to have fun, and who can blame them?

Not me, that's for sure, because I've always been a puzzle fan. Bethan, my lovely editor at Head of Zeus introduced me to a mystery game called Cryptic Killers about a year ago, and I've enjoyed several games of that. Back in May, I took part in a Murdle game hosted by the creator, G.T. Karber. Ten days ago I was chatting with my editor at HarperCollins about this trend and last week (after an encouraging lunch meeting with the British Library folk and then a coffee with Bethan and the Head of Zeus and their publicist) I rounded the day off in style, as I had the pleasure of participating in an interactive mystery game hosted by my agent James Wills and his company Watson, Little.

This was a game devised by Jury Games and it took place at the Theatre Deli in London. The literary agents were joined by a group of their clients, all of whom are crime writers. A very convivial bunch of jurors, and we had a lot of fun trying to figure out what was going on. How did we do? Ah, that would be telling...

Just as enjoyable were the conversations in a local pub after the game was over. I had the pleasure of chatting with a group of lovely people, including Alex Marwood, Ajay Choudray, Victoria Dowd, Luke Chilton, and Alex Pavesi. I've often made the point that the life of a writer has plenty of downs as well as ups, but that was one of those days when I was acutely aware that overall it's a hugely pleasurable existence.

.JPEG)

.JPEG)

.JPEG)

.JPEG)

.JPEG)

.JPEG)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)