Thanks so much to you, the readers of my blog, for following my posts during the past twelve months. 2021 has been a strange year for almost all of us. On Christmas Eve, I was taking my daily walk (something I've done ritualistically for the past two years, even before the pandemic struck) ruminating on an irritating email when I bumped into a couple I've known for around 25 years. The husband, who is about my age, told me he's suffering from a brain tumour. The courage he's showing made me feel remorseful about my grumpy reaction to that email. A reminder that it's so important to concentrate on appreciating the good things in life while one can. And despite being unable, again, to see many friends in person, there have at least been plenty of those good things over the past year.

This year saw the UK publication of The Crooked Shore, the eighth Lake District Mystery, but the first for six years. The break seems to have done me good - the reviews in The Times and elsewhere have been terrific, which is especially rewarding given that this book is rather different in some ways from its predecessors. I hope this augurs well for the book's US publication next summer, under a different title.

This time last year, I never anticipated being commissioned by Otto Penzler of The Mysterious Bookshop to write a Bibliomystery for him. The result was The Traitor, a novella which was great fun to write (while visits to Llandudno and Shropshire in the first half of the year provided me with some of the settings). It introduces a 'book detective', Benny Morgan, who may return in the future. I don't have any specific ideas for Benny just yet, but he's a character with, I feel, plenty of potential. And I just heard from Otto this week that the story is shortly to be released on audio.

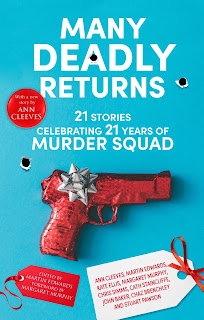

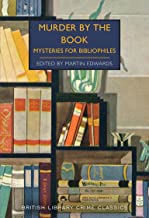

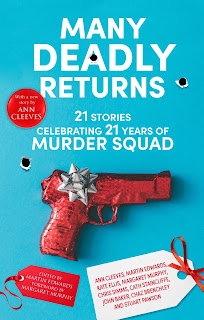

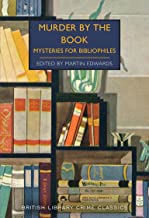

In terms of anthologies, I edited Many Deadly Return, celebrating Murder Squad's 21st anniversary, and including three stories of mine. The book's launch in Whitley Bay (see the photo above) was memorable, as well as providing a good reason for a few days in the north east. There were also two British Library collections, Guilty Creatures and Murder by the Book. Lee Child picked 'The Locked Cabin' for inclusion in The Best Mystery Stories of the Year 2021, while 'The Bookbinder's Apprentice' featured in Daggers Drawn.

Howdunit won one crime writing award (the CrimeFest HRF Keating Award) and was nominated for five others, four of them in the US. This was a source of huge pride, both personally and on behalf of the Detection Club members who contributed to the book, even though the pandemic meant that I didn't attend a single awards ceremony in person. Over the year I published getting on for twenty introductions to various books and numerous articles, including 'Death by Chocolate', commissioned by Slightly Foxed, who also invited me to speak at their Readers' Day, where I had the pleasure of sharing a bill with Michael Palin. Other subjects I wrote about included Josephine Tey (CrimeReads) and Mary Kelly and CHB Kitchin (CADS) as well as aspects of crime writing craft and my own work.

No overseas travel again this year. Not to worry: I took the decision after the very first lockdown to take any opportunities that were presented for travel within Britain and I found these trips extremely thereapeutic and rewarding in all sorts of ways. Quite apart from the trip to Northumberland and its environs, I spent time in North Wales, the Wye Valley, Harrogate, Ely and the Fens, the Lake District and Derbyshire. There were lovely boat trips in Ely, at Symonds Yat, and around the Farne Islands, plus a steam railway journey through eastern Kent.

This year, unlike last, I also managed to take part in live festivals - at Buxton, Rye (see the photo below with Elly Griffiths, Andrew Wilson, Nicola Upson and John Case), and Torquay - as well as a good many that were online only. The podcasts and online events were many and varied, including Alibis in the Archive (with the brilliant musician and writer Rupert Holmes among the guest speakers) and an interview by Lucinda Hawksley, as well as a writers' workshop for Wirral Libraries.

My interest in workshops was one of the catalysts for Crafting Crime, the online course I've set up with Dea Parkin and her editorial consultancy Fiction Feedback, which recently went live. We've been really pleased by the initial take-up of and reaction to the course and we'll be promoting it more extensively in the coming months.

The longest holiday of the year was spent in the south, with trips to places as different as the ossuary at Hythe and the shoreline at Porlock Weir, enjoyed in lovely weather. A fantastic trip, even if I did under-estimate how long it would take to drive from Rye to Torquay...

It also proved possible to host a couple of meals for the Detection Club. We broke with tradition by having a marvellous lunch at Balliol College, Oxford (see the photo close to the top and the pic with Peter Lovesey below), whose Master, Dame Helen Ghosh joined us and gave an impromptu speech. Dinner at the Ritz in October was great fun, as was spending time in the bar with lovely new members Lynne Truss and Chris Fowler (photo above). The dinner also gave me a chance to meet in person Simon Dinsdale, Kevin Durjan, and Giles Ramsey, with whom I've done several weeks of online lecturing on 'the Art of the Whodunit' during the pandemic.

Plenty to celebrate, then, and plenty to remember fondly - many reasons to feel thankful. And I am.